Global Extent and Impact of Kew Royal Botanic Gardens

Kaleb Rasmussen, Spring 2025

London is home to what can be regarded as the most renowned and prestigious botanical research center and garden across the globe. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens has been around for centuries and is now practically a garden with aspects from six continents within it [7]. Not only does it hold plants from other continents, but it also holds architectural designs and more from different cultures around the world [3]. Today, its extensive living collections, herbariums, and historic glasshouses reflect centuries of exploration and ecological curiosity. Kew Gardens has become both a cultural landmark and a scientific institution of international importance.

Kew began more as a pleasure garden as part of two royal estates, Kew House and the Richmond estate. These two houses were brought together through the marriage of Princess Augusta, the mother of King George III [3]. Around the mid-18th century, Princess Augusta started the formation of Kew as a scientific garden. Princess Augusta’s intentions for Kew to be a scientific institution were supported by her son King George III when he inherited the estate [3]. Augusta’s intentions and George III’s support foreshadowed Kew’s eventual role in imperial plant exchange. One of the most influential collectors and biggest leap in Kew’s imperial exploration and expansion was the first voyage of James Cook aboard the HMS Endeavor.

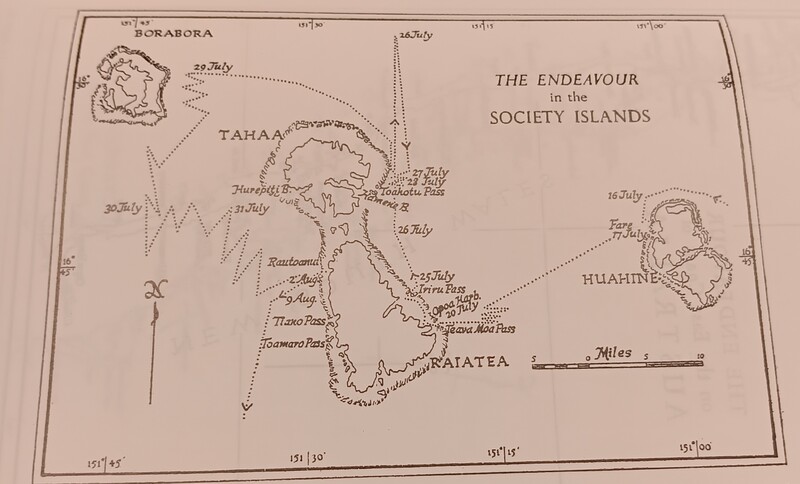

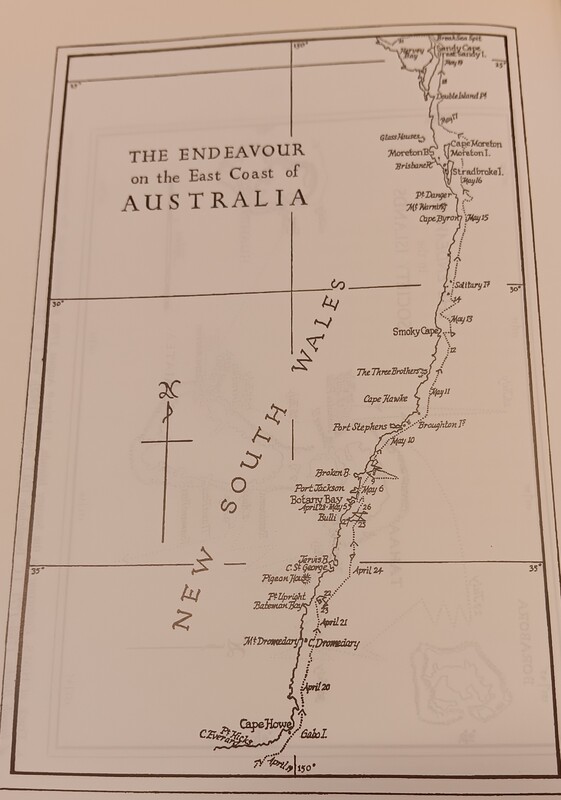

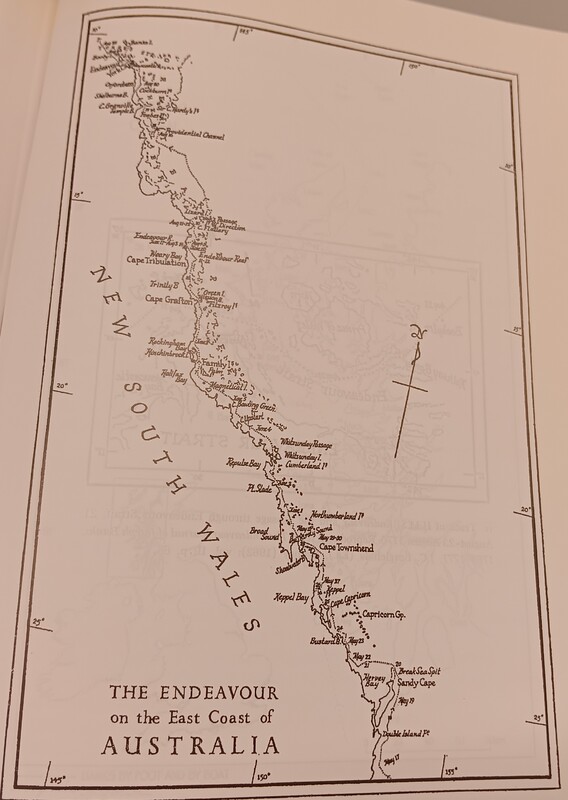

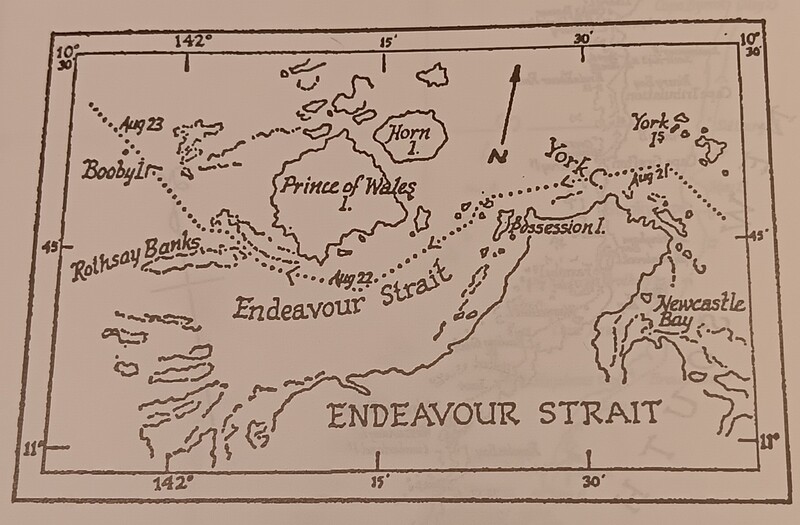

Sir Joseph Banks became one of the most important people in building Kew’s legacy and reputation. In 1768, Joseph Banks accompanied James Cook on his voyage aboard the Endeavor to several continents. He catalogued every plant he came across in each area of each continent they explored and sent back seeds he discovered while in the South Seas [4]. Not only that, but he also noted the lifestyle and culture of the people who they met [9]. When Banks and Cook returned from their voyage, Banks took on a highly active role as the unofficial advisor to King George III (later appointed informal director by King George III [5] and the other gardeners at Kew. Banks used his wealth, connections, and growing influence to transform Kew into a central hub for plant exchange across the British Empire. Little did he know that his efforts would help transform Kew into a central hub for plant exchange and more across the world.

Banks sent collectors across the globe to research, catalogue, collect plants and send back seeds and specimens to Kew for cultivation. Banks’ exploration and collecting on his expeditions resulted in the addition of “about 110 new genera and 1,300 new species” [4]. As a result of Banks’ influence in pushing Kew to become a botanical powerhouse, he caught the eye of Catherine II of Russia. In 1795, Catherine II sent a request to King George III to receive collections of plants and seeds from Kew. King George passed this letter to Banks and put him in charge of this diplomatic exchange, which was planned out for months and ended with Catherine receiving her desired collections from Kew and Kew receiving seeds hand selected by the Duchess herself to cultivate at the gardens [2]. This exchange between Kew and Russia vastly increased Kew’s global influence and standing as a central hub in networks for botanical research and plant exchange.

Thomas Banks continued aiding Kew in their progression up until his death in 1820. One major expedition under Joseph Banks was the breadfruit expedition to the Caribbean in the late 18th century. The goal of this expedition was to transport breadfruit trees from the South Pacific to Jamaica and other areas in the Caribbean to serve as a cheap food source [3]. Kew served as the hub for collecting and distributing these plants to colonial outposts and supported the cultivation and classification of them. Captain William Bligh led two voyages, but only the second one successfully delivered the plants. The successful delivery of the breadfruit plants showed how Kew was intertwined with Britain’s imperial expansion and was further developing as not only a scientific institution, but as a central hub for global plant exchange and botanical research.

Another global expedition centered around Kew was the sending of Cinchona trees to Jamaica to combat Malaria [1]. In the mid-19th century, then director Joseph Dalton Hooker (son of the first director William Jackson Hooker), coordinated the transfer of cinchona seeds and plants from South America to Kew for cultivation. Once they were cultivated, Kew sent seedlings of the cinchona tree to Jamaica and other British colonies. The main goal of this “imperial scientific effort” was to produce quinine locally, which can be extracted from the cinchona tree’s bark and used to treat malaria, to break Britain’s dependence on expensive imports [3, 6]. In 1874, Kew gardener William Nock, who also helped the transfer from Kew to Jamaica, designed the Cinchona gardens where it still stands today with multitudes of extraordinary species residing there [10]. J.D. Hooker continued to follow in his father and Banks’ footsteps, including embarking on expeditions across the sea.

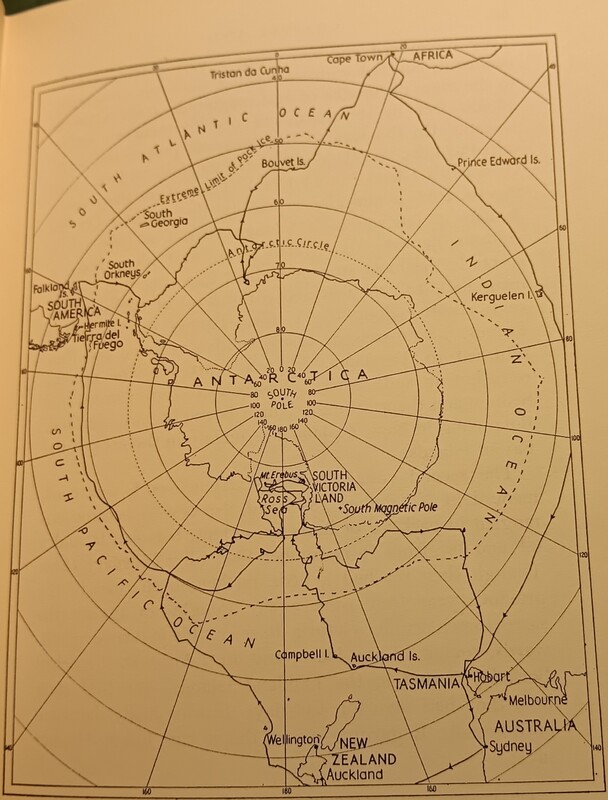

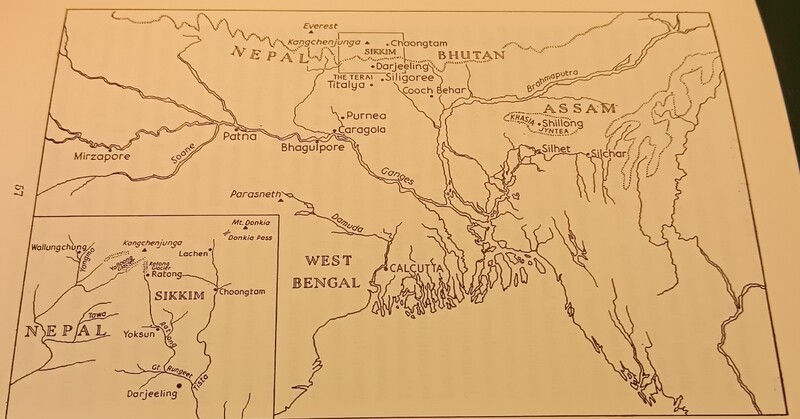

J.D. Hooker’s first voyage was aboard the HMS Erebus in 1839 under Captain James Clark Ross, where they traveled to Antarctica [8]. Hooker served as the assistant surgeon and Kew’s botanist and discovered and collected hundreds of new plant specimens, expanding the understanding of subantarctic plant life [11]. Many regions that Hooker saw on this trip had never been observed by other European botanists. Hooker’s impact and discovery on this Antarctic expedition strengthened his credibility and scientific authority, leading to him embarking on more expeditions to places such as Morocco and India (where he was surprisingly imprisoned for a short time) [3, 11]. J.D. Hooker’s hard work and dedication to Kew led to him taking his father’s place as director and continuation of building and strengthening Kew’s reputation and scientific authority.

Today, Kew holds plant specimens from 10 different countries and regions across 6 continents [7]. Kew has become, quite literally, a garden representing the entire world. None of these feats could have been possible without the botanists, explorers, and researchers who traveled the globe to discover, collect, and study hundreds of thousands of plant specimens and send them back to Kew for cultivation and research. The history of Kew Gardens reveals the deep connection between science, empire, and botanical ambition. From the beginning as Princess Augusta’s pleasure garden to traveling the globe in search of discovery, Kew evolved into a global hub for plant collection, classification, and exchange.

Bibliography

[1] Author, Unknown. Letters describing “Kew (sending of plants to Jamaica)”. National Archives, Kew.

[2] Carter, B. Harold. “Sir Joseph Banks and the plant collection from Kew sent to the Empress Catherine II of Russia, ” 1795, p.281-385, British Museum (Natural History), Wellcome Collection.

[3] Desmond, Ray. “Kew: The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens”. The Harvill Press with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2016.

[4] Fisher, James. “The Legacy: Sir Joseph Banks, the Naturalist Who Created Kew.” Country Life, 8 Apr. 2024, www.countrylife.co.uk/nature/the-legacy-sir-joseph-banks-the-naturalist-who-created-kew-267596. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

[5] Gardens, Kew. “Adventure and Discovery around the World with the Plant Hunters.” Kew, www.kew.org/read-and-watch/adventure-and-discovery-around-the-world-with-plant-hunters. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

[6] Gardens, Kew. “Cinchona Tree.” Kew, www.kew.org/plants/cinchona-tree. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

[7] Gardens, Kew. “Travel the World at Kew.” Kew, www.kew.org/press-media/travel- the-world-at-kew. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

[8] Jones, Cam Sharp. “Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker: Trailblazing Global Botanist and Explorer.”Kew, www.kew.org/read-and-watch/sir-joseph-dalton-hooker-trailblazing-global-botanist-and-explorer. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

[9] Lysaght, A.M. “The Journal of Joseph Banks in the Endeavour”, 2 volumes, 1980, Wellcome Collection.

[10] Press, Associated. “Jamaica’s Cinchona Gardens Are a Wild Treasure.” Deseret News, 17 Jan. 2024, www.deseret.com/2002/7/21/19667305/jamaica-s-cinchona- gardens-are-a-wild-treasure/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

[11] Turrill, W.B. “Joseph Dalton Hooker. Botanist, explorer, and administrator”. 1963. British Library.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this Study Abroad class provided by the UAH Honors College. Additional thanks to my mother and sister, Professor Grimsley, Professor Staton, Charlie Gibbons, the National Archives in Kew, the British Library, the Wellcome Collection, and Kew Royal Botanic Gardens.