Ashton Lucky, Spring 2025

Introduction

Katherine Parr is often merely remembered as the sixth and final wife of King Henry VIII, who is known for being the one who survived the infamous monarch. Yet, condensing her legacy to this one role overlooks her impact on our history. Parr was a devoted scholar, profound author, beloved stepmother, educational advocate, and avid Protestant reformer. Her contributions, rooted in her beliefs, make it clear that she is perhaps one of the most influential queens in history. Despite her achievements, the circumstances surrounding the desecration of Katherine's remains serve as a poor reflection of how the legacies of even the most remarkable and well-known women in history are often diminished. By observing her life, from grand beginning to forlorn end, we can see how there is far more to the woman who was Katherine Parr, and we can begin to reassemble her shattered legacy.

Author's Note: While several spellings of Katherine’s name appear throughout historical documents, biographical books, and other archival records, Katherine herself often signed her name as "Kateryn", a spelling that would correspond to the modern "Katherine." Although there is some debate among historians regarding the preferred form of her name, this essay will use the spelling "Katherine" for the sake of consistency, clarity, and in respect to her own writings.

Of Books and Betrothals: Katherine Parr's Birth to Young Adulthood

Katherine Parr was born around August 1512, the eldest surviving child of Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal in Westmorland, who served as a close courtier to the young King Henry VIII, and Maud Green, who served as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII. While it is possible that Katherine was named after Catherine of Aragon, the difference in spelling suggests that any connection may not have been a deliberate homage. Nevertheless, Catherine of Aragon was named her godmother. The Parr family, then consisting of Katherine, her parents, her younger brother William Parr, who would later become the Marquess of Northampton, and her younger sister Anne Herbert, the future Countess of Pembroke, had strong northern Yorkist heritage, strengthened by advantageous marriages and loyal service during the reign of King Edward IV onward. Each member of the family was or would go on to be extremely prominent in court by some point in time.

After the death of her father in 1517, when Katherine was just five years old, her mother, Maud, assumed responsibility for managing the family estates and raising the children. Maud's approach, independent and practical, left a lasting influence on Katherine, fostering her intellectual curiosity and a strong educational foundation. By early adulthood, Katherine would be fluent in English, French, and Italian. In her pastime, she also studied Latin and Spanish and developed a keen interest in medicine.

At the age of twelve, Katherine was expected to have a marriage arranged, but her mother could not afford the necessary dowry to secure such a match. Instead, a match was arranged for her brother William. However, by the age of either sixteen or seventeen, Katherine was married off to a distant kinsman, Sir Edward Burgh, in Lincolnshire.

Twice Wife and Widow: Katherine Parr's First Two Marriages

The Burgh family (also spelled "Borough" in several records) was not without a complex legacy. Edward's father was Thomas Burgh, First Baron Burgh of Gainsborough, bodyguard of Henry VIII, and eventually the Lord Chamberlain to Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII. He was also a passionate supporter of the Protestant Reformation. In May 1533, during the coronation of Anne Boleyn, Thomas was severely rebuked for tearing off the profound Catholic Catherine of Aragon's coat of arms from her ceremonial barge.

But it was not just Edward's father who had complications. Several members from both sides of Edward’s lineage, including those on his mother Agnes Tyrwhitt’s side, were declared legally insane. In the case of Edward himself, it has been strongly theorized that he was homosexual rather than insane, giving an explanation as to why he and Katherine did not have children despite their age. Although there is no definitive evidence, it is plausible that his family concealed his sexuality by labeling him as mentally unwell, as this carried significantly lighter consequences at the time, such as house arrest, rather than death.

By 1533, just four years into their marriage, Edward would die at the age of twenty-five, likely due to poor health throughout his twenties. Around the same time, Katherine's mother had also passed away. This left Katherine a childless widow, having lost both her mother and her husband. While her siblings had begun to establish themselves at court in southern England, tradition held that Katherine, a young and relatively poor widow, would stay with older relatives. Separated from her siblings, Katherine would live at Sizergh Castle in Cumbria, in northern England.

In 1534, at the age of twenty-one, Katherine would be married once again, this time to the "elderly" forty-one-year-old John Neville, Third Baron Lord Latimer.

The Neville family was among the oldest and most powerful in northern England, known for their military service and political ambition, even at the expense of royal favor. John had come to court as one of the King’s gentlemen-pensioners and was knighted during Henry VIII’s French campaign in 1513. He became Knight of the Shire for Yorkshire in 1529 and joined the Council of the North the following year. In 1530, he signed the petition to Pope Clement VII supporting Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon.

This marriage made Katherine a stepmother for the first time. She helped raise John’s two children from his first marriage: John Neville, Fourth Baron Latimer, who was thirteen or fourteen at the time, and Margaret Neville, who was eight or nine years old. Margaret would be the first of many of Katherine's stepchildren who would come to love her as their mother. In her will in 1545, Margaret wrote: "I was never able to render her grace sufficient thanks for the godly education and tender love and bountiful goodness which I have ever more found in her." This is but one of the many instances where Katherine was fondly spoken of in writing by her stepchildren.

In 1536, Katherine and her family would be caught up in the Pilgrimage of Grace, an intense, large-scale northern uprising in support of Catholicism and opposition to the English Reformation. Rebels captured her husband and held Katherine and the children hostage in their own home. John attempted to mediate between the crown and the insurgents, but this involvement led to suspicions of treason. After a royal inquiry in November 1536, he was granted amnesty. The ordeal, however, forced the family to relocate south, bringing Katherine closer to the court and her siblings.

This situation may have also been the catalyst for Katherine's profoundness and conversion to Protestantism, turning away from her Catholic beliefs. Sometime during this marriage, Katherine had gathered a circle of other like-minded reformers, likely due to her avid interest in religious disputation. Her passion for religious discussion, and likewise education, would also be passed on to Margaret.

Following the rebellion, John’s health began to deteriorate. His frequent absences for business also left Katherine managing the household and spending more time in the royal court. After his death in 1543, Katherine inherited his title and estates, making her a wealthy widow and one of the most eligible women in the country.

Katherine’s presence at court during this time had not gone unnoticed. Thomas Seymour, First Baron of Sudeley, the Lord Admiral of England, the "most dashing man in Henry VIII's court," brother of Henry VIII's third wife, Jane Seymour, and uncle to the future King Edward VI, had expressed interest in her. So, too, had King Henry VIII himself. Shortly after the execution of his fifth wife, Katherine Howard, the king had declared his wish for an older woman. He would go on to send Katherine his first gift two weeks before John's death.

Duty Over Love: Katherine Parr's Reign as Queen

After two obligatory marriages, Katherine finally had the chance to marry for love. Of her options, Katherine much preferred Thomas Seymour. More than likely, she and Thomas were introduced in court, possibly through her brother, William. During this period, the two shared an intense courtship of which she seriously considered accepting.

However, the Seymour family was far from saintly, and Thomas was no exception. Born to Sir John Seymour and Margaret Wentworth, he was the fourth of six sons. Having a smaller position in the family would cause Thomas to be power hungry and deeply ambitious, which at times manifested in extremely reckless behavior, much more prominently in later years. Nonetheless, Thomas was charming, persuasive, and despite his age, he had never been married.

His charm had seduced Katherine, however, even as the king began making advances. In May 1543, Thomas was forced away from the courts and sent abroad by the king, appointed ambassador to the Habsburg court in Brussels. Later, when war erupted between England and France, he was named Marshal of the English army in the Netherlands on June 26, 1543.

Throughout this time, Henry VIII continued his pursuit of Katherine. The exact circumstances of how the two met, however, has been lost to history. Some suggest that the two may have met in court, through either her then-husband, John, or through one of her siblings. Others place their meeting during Henry VIII's visits to his daughter Mary’s household, where Katherine may have served as a lady-in-waiting. Katherine is also said to have petitioned the king on behalf of her uncle, Sir George Throckmorton, in 1540. Regardless, according to members of the royal court, “It was not so much choice as necessity” that led the king to marry a widow. Katherine’s previous marriages reassured the court that she was not a virgin, an important factor given Henry’s turbulent history with his previous wives’ alleged and proven affairs.

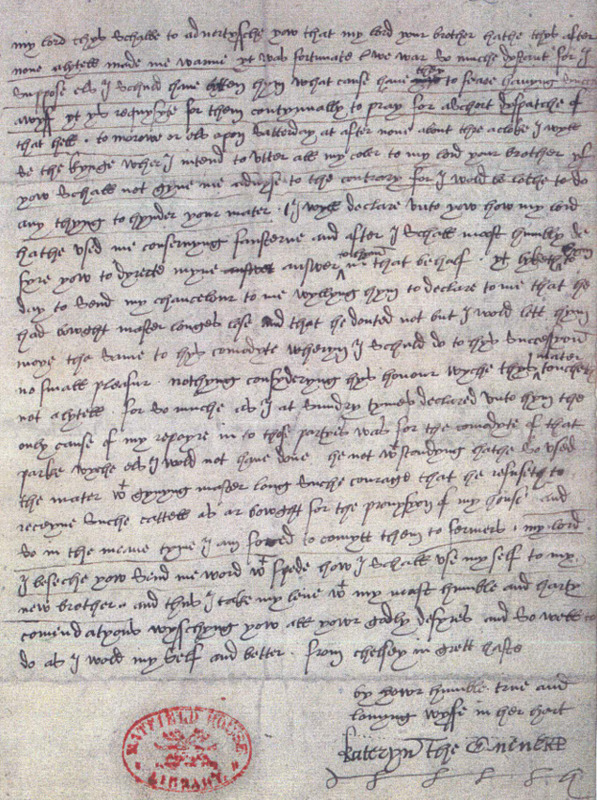

Ultimately, Katherine chose duty over love, marrying the king in a private ceremony in the Queen’s Closet at Hampton Court on July 12, 1543, attended only by close friends and family, including the King’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. In a letter to Thomas, supposedly in February 1547, Katherine expressed her reasons for marrying the king:

"For as truly as God is God, my mind was fully bent the other time I was at liberty to marry you before any man I knew. Howbeit, God withstood my will therein most vehemently for a time and...made me to renounce utterly mine own will, and to follow His will most willingly...If I live, I shall declare it to you myself."

This letter reveals Katherine’s deep affection for Thomas as well as her religious devotion, which guided her decision between love and what she and the court deemed her obligation. Notably, no known correspondence exists between her and Thomas during this marriage, attesting to her loyalty. Katherine's motto as queen was fittingly: "To be useful in all I do," and as her emblem, she chose a crowned maiden with a Tudor rose. Upon becoming queen, Katherine also appointed her first stepdaughter, Margaret Neville, as a lady-in-waiting.

Katherine’s marriage was widely accepted, and she even earned admiration from Eustace Chapuys, imperial ambassador notorious for his disdain of Anne Boleyn and refusal to even speak her name. A staunch supporter of Catherine of Aragon and her daughter Mary, Chapuys found favor with Katherine despite their religious differences, of which he publicly loathed Anne for. The one notable dissenter was Anna of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife, who is often believed to be the queen with the most amicable outcome. Despite being married for only six months and given a generous settlement with the assurance that she would not return home to Germany in fear of war, Anna had greatly hoped that she might be reinstated as queen after the execution of Katherine Howard. Bitterly disappointed, she openly criticized Katherine, often calling her "no great beauty" to those around her. Undeterred, Katherine won the admiration of many and became a respected consort.

When Henry VIII originally married his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, he was regarded as a kind and devoted husband and father. But following a severe jousting accident during his marriage to Anne Boleyn, in which he received a fractured skull from a horse rolling over him, his temperament worsened. Likely, this is the reason why Henry VIII was so volatile toward his future wives. Additionally, by the time of his marriage to Katherine, his age and health had caught up to him, leaving him with aggressive sores and ulcers across his left leg, which he could barely use, leading to his well-known and grand size. This also made him extremely irritable.

Despite these challenges, Katherine gained his favor as a wise and compassionate companion. He would even give several members of her family much higher positions and statuses. Throughout their marriage, Henry VIII's leg continued to fail him, and at some point in time, Katherine moved out of her queen's quarters and into a smaller bedroom to be closer to his own king's quarters. It has also been suggested that Katherine was the prime reason that the king began to wear glasses, as she encouraged him to improve his quality of life, however possible. Her knowledge of medicine from a young age also helped during this time, earning Katherine the nickname later on as "the nurse," as she alone was the only one of whom Henry VIII would allow to dress his leg, even among his doctors. In a private letter by Sir Thomas Wriothesley, First Earl of Southampton, he describes Katherine as, “A woman, in my judgement, for certain wisdom and gentleness most meet for his highness; and sure I am his majesty never had a wife more agreeable to his heart than she is.”

It is quite obvious that Katherine supported Henry VII both personally as well as politically. Often, Katherine was referred to by the king as his sweetheart, and he trusted her with his children and his country, as Queen Regent-General when he was away in France at war. For Katherine, this was a sign of remarkable trust from Henry VIII. Besides Catherine of Aragon, no other of his wives had ever been Queen Regent. During that time, Katherine signed five royal proclamations, supporting her husband's war effort while also overseeing several domestic issues, such as tensions on the Scottish border.

Some historians argue that her continuous appearances, independence, and other strengths in court, which were likely modeled after her mother, are what inspired the separate reigns of both Mary I and Elizabeth I down the line. Aiding this theory, during the summer of 1544, during Katherine's regency, Elizabeth spent time with her stepmother at Hampton Court, and for the first time, she visited a royal palace with a queen, not a king, presiding over the court.

However, as we have seen before with Margaret, Katherine was not just a great queen, but also a great stepmother. It is inherently noticeable during her marriage to the king. Katherine was incredibly devoted to her stepchildren's education and familial ties, consistently working to improve the treatment of her stepdaughters. Reports from Henry VIII's court show that Katherine was a key player in the king's decision to restore his daughters to the line of succession, a choice that supported both women's future claims to the English throne as Mary I and Elizabeth I and caused huge implications for the Tudor dynasty. It also helped Mary and Elizabeth reconcile with their father. She also facilitated family unity by organizing shared dinners, which was an uncommon practice among royalty, who typically lived separately.

Despite theological differences, Katherine and Princess Mary were quite close, sharing a bond rooted in their similar age, beliefs on education, and mutual respect. This may be why many believe that Henry VIII met Katherine while she was attending Mary's home years before their marriage. In a letter, dated September 1544, Katherine writes to Mary, explaining how she would like to visit soon, and hopes to in the winter. She also thanks Mary for her recently received gift of a purse. This letter shows their fondness for one another.

Katherine's relationship with Princess Elizabeth was particularly profound, as four of the five surviving letters written before the young girl turned sixteen were addressed to Katherine. Additionally, in later years, Elizabeth would even choose to live with her. Katherine’s passion for education and religion would go on to shine through to Elizabeth as well in later years.

Prince Edward VI also shared a close bond with Katherine. The two exchanged frequent letters in Latin as they learned the language together. In one particular letter, Edward apologizes to Katherine for not writing for several days, suggesting that they exchanged letters possibly daily. He then even goes on to refer to her as his “dearest mother.” Considering Edward’s biological mother died in childbirth, and neither of the queens after her particularly cared for children, this is likely a true statement. In a separate letter, Edward adds to this, confirming: "Wherefore, since you love my father, I cannot but much esteem you; since you love me, I cannot but love you in return; and since you love the word of God, I do love and admire you with my whole heart."

Katherine also restructured the curriculum for the two younger children of Henry VIII to have a more humanist model of education. She also highly encouraged their translation skills by having them translate the works of Erasmus. Although both of the children's biological mothers were Protestant, Katherine's encouragement here may have influenced their reigns and sparked the bloody feud between the two siblings and Mary in later years. It is evident that Katherine had a lasting admiration for all of her stepchildren. In an observation noted by one historian in the Sudeley Castle records, it is stated that "There is no doubt that all of her stepchildren, both Latimer and Tudor, loved her."

Katherine was also a profound supporter of the University of Cambridge. In a letter dated February 1547, during which the school was in great danger of dissolution, Katherine writes to them, ensuring them that she had approached the king to ensure that money would arrive soon. This shows how her passion for learning extends past her family and to the people as well.

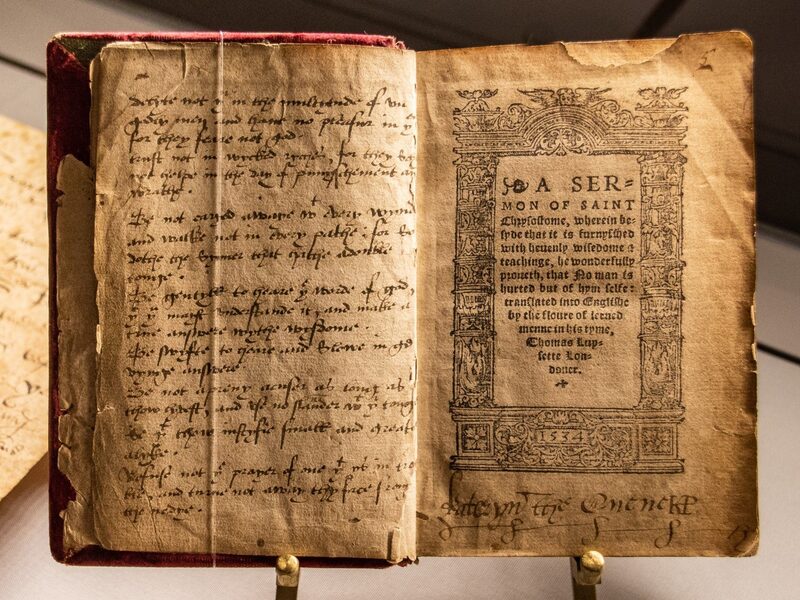

But Katherine was not just a great mother and scholar, she was also a profound author. In 1544, she anonymously published her first religious compilation, Psalms and Prayers, an English translation of the Latin Psalms originally published by John Fisher around 1525. Although published anonymously, her handwriting is quite distinctive, and among other pieces of evidence, this ties her as the author of the compilation. The book would make Katherine the first woman to publish her work in English with the intention of influencing the public. With the help of Elizabeth, as a testament to Katherine's more advanced education granted to her, the work would go on to be translated into several languages, including French and Italian.

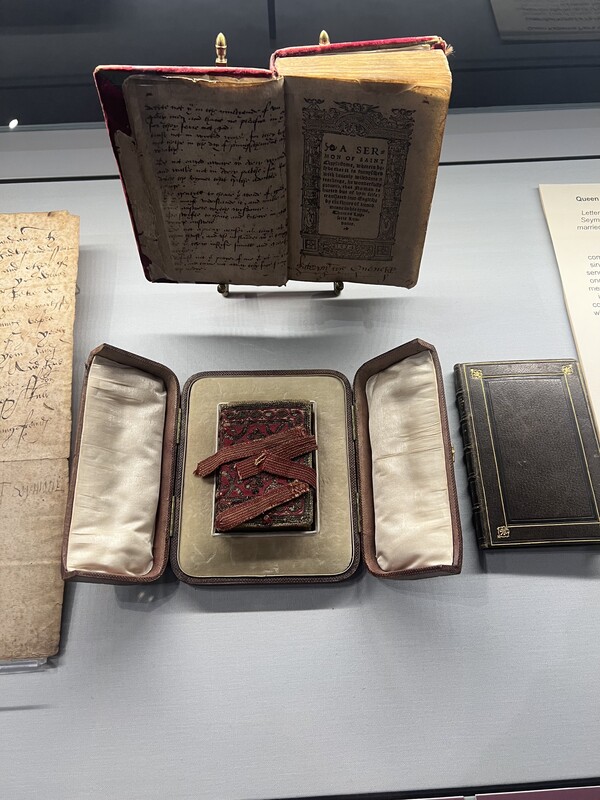

On July 8th, 1545, Katherine personally published Prayers and Meditations, a compilation of texts and verses that she assembled for personal, reformist devotions. Nineteen editions were published by 1595, although the original manuscript remains incomplete.

These works make many historians believe that although Jane Seymour is known as the “Protestant Queen”, the title would be more accurate had it been given to Katherine. Although Jane was also quite sound in her beliefs, Katherine was an avid writer and fought against many who, during this time, believed that "lesser people should not read the Bible in fear of heresy." While many in the courts upheld this belief, Katherine continued her study groups.

This would soon put Katherine at risk. Although the king was fond of his wife, he was still a religious conservative at heart. As his health continued to deteriorate, he would grow increasingly irritated with Katherine's passionate debates about reform. Many other conservatives at court felt threatened by the prospect of further "heretical" Protestant influence in the English church and with it, Katherine, who had had much success during her time as Regent-General.

In 1546, the situation took a turn for the worse when Henry VIII expressed to the Catholic Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, his frustrations. According to John Foxe's Book of Martyrs, released in 1563, Gardiner and his co-conspirators jumped on the opportunity to implicate Katherine for heresy, quickly launching an investigation and searching for evidence of radical religious texts in the rooms of Katherine's ladies.

They also interrogated, imprisoned, and tortured Anne Askew, a protestant preacher, in the Tower of London. Anne would go on to be burned at the stake for heresy rather than implicate the queen. Undeterred, Gardiner would present his evidence to the king and secure a warrant for her arrest. By chance, Katherine's allies caught wind of the warrant and informed her of the plot. Understanding the importance of the situation, likely with the king's previous wives as examples, immediately, Katherine would take to her bed with a plan, and proclaim she felt terribly ill.

When Henry VIII would arrive by her bedside, Katherine asked if he was angry with her, promising that she only debated with him to learn from him and take his mind away from his illness and other injuries. She also exclaimed how she was a "silly, poor woman" and the king was her "only anchor...next to God" for good measure. Moved by her words, Henry VIII forgave her, and at her side he proclaimed: "And is it even so? Then Kate, we are friends again."

When officers came to arrest her, he reportedly lashed out at them, calling them “Knave, Fool, and Beast!” By deferring to her husband, Katherine displays her cleverness and survives what many of the wives before her could not: a plot to remove a queen from Henry VIII's side. It is said that he profusely apologized to his wife after the event, presenting her with a plethora of jewelry.

Despite her serious responsibilities, Katherine enjoyed music, dancing, and fine clothing. She even had her own consort of Italian musicians. In particular, she had a strong passion for shoes, as one financial report showed that she ordered nearly fifty pairs of shoes in one year. She also adored animals and practiced embroidery in her free time.

Katherine is also noted as the first recorded queen to have commissioned several portraits by female artists. Although debated, it is believed that these artists include Susannah Hornebolt, Levina Teerlinc, and Margaret Holsewyther.

On January 28th, 1547, three years, six months, and five days after their marriage, Henry VIII would die from natural causes. Katherine was away celebrating the Christmas season, as was common for royals. Although her tenure as queen was not long, this was still longer than several of the king’s other wives. The King’s death was concealed for several days as arrangements were made, and Edward VI ascended the throne at the age of nine.

One-Sided Romance: Katherine Parr's Final Marriage

Immediately following the king's death, Katherine would once again be named Queen Regent. It was not long before Thomas Seymour would choose to pursue her. Katherine was now powerful, incredibly wealthy, and once again a widow, and Thomas, still the fourth eldest brother of six, seemed to jump at the opportunity of this advantageous match. For him, this was likely a "stepping stone" marriage, one where he could improve his status in court and potentially gain insight for a more powerful marriage down the line. Thomas assured Katherine that he had remained single during their time apart out of loyalty to her. In truth, however, he had sought marriages with both Anna of Cleves and Princess Mary during that period. Yet, perhaps due to her previously unromantic and strained prior marriages and the rekindling of their earlier romantic connection, Katherine believed him.

By February, the two were exchanging letters addressing each other as husband and wife, likely signifying a forthcoming marriage rather than a finalized one. After a brief mourning period in which Katherine refrained from public flirtations in order to prove she was not carrying Henry VIII's child, she and Thomas were secretly married. It is believed to have taken place in May at her Chelsea Manor, done without the permission or approval of the new king.

Though secret, the marriage was known to a select few within their circles. Katherine’s sister Anne and her close friend Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, even teased Thomas in private about the union. Slowly, the couple dropped hints to Edward VI, with Thomas paying a servant to persuade him about the match. When asked who he wanted his uncle to marry, Edward would often make comments such as "My lady, Anna of Cleves" or "My sister, Mary, to change her opinions [on religion]." Finally, on June 25th, Edward settled on his stepmother, Katherine, and gave his blessing for their marriage. Once it was revealed that the two had gotten married, but not when, Edward was delighted at the match.

Not everyone shared his sentiment. Thomas's older brother, Edward Seymour, then Lord Protector of England, was furious at not being told about the marriage sooner. Knowing that Katherine had sent her jewels, including her and Henry VIII's wedding rings, heirlooms from his previous wives, and gifts from her mother, Maud, to the jewel house in the Tower of London for safekeeping during the mourning period after Henry VIII's death, Edward and the Privy Council withheld Katherine's jewels from her in retaliation, claiming them as state property, merely lent to Katherine. Nevertheless, this did not stop Edward from gifting several of the jewels to his wife. In addition, they also removed any power Katherine might have continued to have as queen.

The situation made Katherine livid. Her attempts to recover the jewels led to a prolonged and bitter dispute between Katherine and her brother-in-law. In one letter, Katherine writes to Thomas that had his brother and her been closer at a meeting, she may have bitten him out of frustration. The dispute would continue for years, and despite her and later, after her death, Thomas's attempts, the jewels were never recovered.

Months after Henry VIII's death, and with the behest of her brother, William, and her close friends, Katherine, the Duchess of Suffolk, and William Cecil, First Baron Burghley, Katherine would still go on to continue her publications. On November 5th, 1547, she published her final work: Lamentations of a Sinner. It acted as a full pronouncement of the queen's Protestant beliefs in the form of a meditational discussion. This work would go on to spark controversy because of its religious views and Katherine's public self-debasement of her sins, which embraced the Lutheran concept of justification by faith, which was seen as unusual for a royal figure.

At this time, Katherine also served as the guardian and educator of both Elizabeth and Lady Jane Grey, her ward and Elizabeth's cousin. Jane, fourth in line to the throne by Henry VIII’s will, would briefly ascend as the “Nine Days’ Queen” after Edward’s death, chosen for her Protestant faith and later executed by Mary I for her own Catholic beliefs. Although argued, by technicality, this makes Katherine the protector of the first and third queens of England.

However, this period is marred by the disturbing behavior of Thomas. He began harassing Elizabeth, who was only thirteen at the time, visiting the young girl in her bedroom in his night clothes, stealing the room key from her, touching her inappropriately, and stealing kisses from her. It is possible that he even forcibly attempted to consummate with her. Many believe he intended to manipulate Elizabeth into a future marriage, hoping to elevate his own political standing should she ascend to the throne. It has also been said that Thomas would encourage Katherine to join him in his "tickle fights" with the young girl, which Katherine occasionally did, assuming that these episodes were innocent.

When the truth was revealed in 1548, Katherine sent Elizabeth away, both to protect her own marriage and to preserve Elizabeth's reputation. Despite the belief that this event ruined Katherine and Elizabeth's relationship with one another, in one of the few surviving letters from before Elizabeth turned sixteen, just three months before Katherine's death, Elizabeth wrote to her, signing off on the note as "Your humble daughter, Elizabeth." Although the situation may have strained their relationship, throughout this letter and several others, it is clear that their relationship was not completely destroyed.

The Price of Motherhood: The Death of Katherine Parr

In December of 1547, at the age of thirty-five, Katherine became pregnant for the first and only known time. The couple was overjoyed, though Thomas expressed concern over her health in letters, hoping the baby would be small to ease her labor. Both Mary and Elizabeth also wrote to Katherine often, with loving concern for her well-being.

Amid fears of plague, Katherine relocated frequently before settling at Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire with the eleven-year-old Jane. Thomas, during this time, was away, attempting to get a marriage agreement confirmed between Jane and his nephew, the king, to receive a full sum from her father as the dowry. Meanwhile, Katherine decorated the nursery for her child at Sudeley "as if she had been still Queen Consort of England," according to many witnesses. There were fair tapestries, ornate chairs, cushions of gold, and a gilded cradle.

On August 30th, 1548, Katherine gave birth to her first and only child. Although she wrote to Thomas that it might have been a boy, the baby was a girl. Katherine was still ecstatic. The daughter was named Mary, in honor of the Princess, and Jane was deemed the godmother.

But although the couple would be excited to welcome their child, Katherine would soon fall ill. It is thought that she contracted childbed, or puerperal, fever from her doctor's dirty hands. Over the next few days, Katherine suffered from paranoid ravings and delusions about her husband and servants. She claimed in this time that her servants were laughing at her, and that Thomas wished to cause her harm. This would later lead to rumors that Thomas had poisoned Katherine, however, this is unlikely, as these rumors were common at the time and were even suspected of Henry VIII after the death of Catherine of Aragon.

On the early morning hours of September 5th, 1548, Katherine, "lying on her death-bed, sick of body, but of good mind and perfect memory and discretion," verbally dictated her will to her physician, Robert Huych, and her chaplain, John Parkhurst. In this will, she dedicated all of her belongings to Thomas. According to an anonymous source from the time, Katherine would then die sometime between two and three in the morning at the age of thirty-six, just six days after her daughter's birth.

Katherine's body remained in her prayer room until the arrangements for the funeral were in order. Her body was then wrapped and buried in a lead coffin within the chapel on the grounds.

Her funeral is known as the first royal funeral according to Protestant rites. The chapel was hung with black cloth of the emblems of her marriages, had an offering table that donated to the poor (which was so unheard of at the time that the Bishop of Exeter, Miles Coverdale, had to explain it to the guests), and had choirs who sang psalms in English rather than Latin. Te Deum was sung as her body was laid to rest, a sign of a true Protestant burial. It also took place just two days after her death, and all within one morning. This was unusual for a royal figure, whose funerals were normally grand gestures.

Soon after her death, her chaplain erected an alabaster monument in the chapel in her memory. In Latin, it read: “In this new tomb the royal Katherine lies; Flower of her sex, renowned, great and wise; A wife, by every nuptial virtue known, And faithful partner once of Henry’s throne, To Seymour next her plighted hand she yields - Seymour, who Neptune’s trident justly wields; From him a beauteous daughter bless’d her arms, An infant copy of her parent’s charms. When now seven days this infant flower had bloom’d, Heaven in its wrath the mother’s soul resumed.”Here, the description reads that Katherine died seven days after the birth of her child. This has raised questions about conflicting dates. Either her child’s birth, her death, or the inscription itself may be incorrect.

After her death, it is believed that her daughter, Mary, remained at Sudeley Castle until March of 1549, when her father was executed after being convicted of treason. Thomas had tried to overthrow his brother as Lord Protector. After attempting and failing to secure the marriage between his nephew and Jane, Thomas kidnapped Edward VI, smuggled money to him, and killed the boy's dog, all in an effort to personally influence the young king. After the debacle, he was sent to the Tower of London with thirty-three charges of treason, where his own brother, Edward, signed him as guilty. At Thomas's execution, Elizabeth supposedly stated: "This day died a man with much wit and very little judgement." A profound statement with an accurate description of what led to the man's demise.

On the eve of his execution, Thomas requested that his daughter, Mary, be given into the care of Katherine's close friend, the Duchess of Suffolk. A few days later, Mary was sent to Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire at six months old. This was done with much reluctance from Katherine, the Duchess, as all of Thomas's wealth and possessions had been reverted to the state after his execution, meaning that there was no money given to the Duchess to provide for Mary and all of her servants who came with her. After she pleaded, money was assured to her by the courts, however, it was never delivered.

On January 22nd, 1550, Lady Mary Seymour was restored to her rightful position, and all of her father's possessions were given to her by an act of Parliament. At the time, she was only a year and four months old.

It is believed that Mary died at around the age of eighteen months and may have been buried in the Tudor Chapel at Grimsthorpe. Her cause of death remains a mystery, as historians are still unsure whether or not Mary even died at all during this time. However, the Privy Council issued a warrant for the expenses of her household around March 17th, suggesting this to be true. Unfortunately, the fate of Mary Seymour remains uncertain, as there are no remains of the Tudor Chapel today.

Additionally, under Queen Mary I’s reign, Katherine, the Duchess of Suffolk, had to flee the country as the queen had begun killing those of Protestant faith, like the young, Nine-Days'-Queen, Jane. Mary I also ordered Grimsthorpe to take account of the Duchess' estate and destroy many of the records left behind. This likely also destroyed the whereabouts of the baby, whether deceased or relocated. Other papers were stored at Wilton House, which was destroyed in a fire in the 18th century, also destroying any additional hope for locating the baby.

Several families have tried to claim descent from Katherine Parr through Mary, but there is no historical evidence that confirms this, even after a manhunt was conducted for a reward for evidence.

Although there is no record of Mary after the age of two, an inscription, supposedly from her tomb, has been located. It reads: “I whom at the cost / Of her own life / My Queenly mother / Bore with the pang of labour / Sleep under this marble / An unfit traveller. / If Death had given me to live longer / That Virtue, that modesty, / That obedience of my excellent Mother, / That Heavenly courageous nature / Would have lived again in me. / Now, whoever You are, / Fare thee well / Because I cannot speak anymore, this stone / Is a memorial to my brief life.” Unfortunately, this likely confirms that after she was orphaned by her parents, Mary likely died amongst the many other young children of the 16th century.

Untouched by Time, Destroyed by Man: The Grave of Katherine Parr

After her burial, the location of Katherine's tomb was lost to time. More than two hundred and thirty years after her death, her coffin was supposedly uncovered in the summer of 1782 by a group of lady sightseers among the "romantic ruins" of Sudeley Castle that had been plundered during the English Civil War by the English statesman Oliver Cromwell's men. The ladies had then persuaded a local farmer, John Lucas, who tended to the land, to dig under the remaining chapel wall and remove the alabaster panel attached to it.

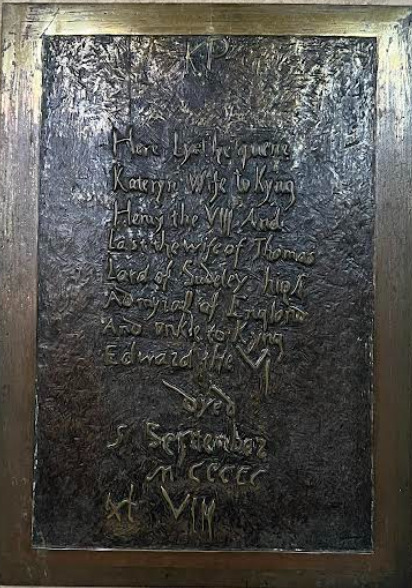

Just barely a foot under the surface of the wall was Katherine's leaden coffin, practically untouched despite its placement. A piece of the inscription simply read: "Here lyeth Quene Kateryn, Wife to King Henry VIII."

The next year, the owner of the castle, Lord George Pitt, was told by his agent, only known as Mister Brooks, about the coffin. Eager to have it investigated, he sent Brooks out, who was joined by John Lucas, who lived in the outer castle. The leaden coffin was then completely pried open with John's bare hands. This offended Brooks, who noted later that he was very displeased with the actions of John, who he assumed would only wish to find the coffin and report it back to Lord Rivers. John would then go on to cut through the six or seven layers of cerecloth covering Katherine's body to discover that it was practically perfectly preserved. In writing about the event, Brooks would note that her skin was "white and moist."

This investigation caused the body to decay greatly, as the tomb was most likely left open. Although it was requested that the grave have a stone slab placed over it to prevent further improper inspection, the order was never executed. Some believe the tale of the ladies and the farmer was fabricated to deflect blame from Brooks and Lucas. Nonetheless, this early desecration heavily foreshadowed the violations that had yet to come to Katherine's body.

In 1784 and again in 1786, the tomb was reopened. The first time, the cloth around her face was cut away, revealing relatively still-preserved teeth, eyes, and facial structure. By the second opening, her face had already deteriorated. Reverend Doctor Treadway Nash documented this decay, explaining that her face had been completely destroyed, with her teeth rotting and falling away. He also reported that the grave must have originally been buried deeper, but had risen over time as the earth had shifted. The Reverand immediately ordered reinternment for the body, but failed to recover the cerecloth around her body and fix the leaden coffin to cover her.

It is here, though, that Katherine's height was discovered as her coffin was found to be "quite petite" in size, suggesting that Katherine must have been around 5'4. Years later, however, a reconstruction of the tomb would find that the coffin may have been longer, destroyed by the wear and tear over time, which possibly disrupted the measurements. With this new information, it is suggested that Katherine may have been 5'10. Nonetheless, with either of the two heights, Katherine would have been the tallest of Henry VIII's wives as we know them.

In 1792, the body would continue to be disturbed, this time with an attempted theft of the body. Finally, the tenant who owned the castle had had enough, and he hired a group of inebriated men to rebury the coffin. Instead, the men desecrated her remains, ripping out and stealing Katherine's hair, knocking out and stealing her teeth, pulling off her head and arms, and stabbing an iron bar through her body. They finished the job by burying her coffin upside down.

The macabre treatment of Katherine's new burial is gruesome and acts as a profound testament to how women are often disrespected in history.

According to local lore in Winchcombe, each man involved met a dreadful end for their improper and cruel actions. After supposed hauntings, some of the stolen items were returned, including a fragment of Katherine's tooth, a locket containing a piece of her hair, and an emblem of Katherine's, also containing her hair.

Despite the horrifying circumstances, these fragments have offered modern historians rare insights. With the preservation of her locks of hair, we have been able to identify that Katherine had blonde or auburn hair that tended to curl naturally. At the very least, we have been able to preserve a part of Katherine, even today.

In 1817, Reverend John Lates, Rector of Sudeley, sought to end the violations for good. He ordered the removal of the coffin and had it placed into a fine stone vault, which was then carefully and securely closed. In just thirty-five years, Katherine's body had gone from pristine condition to nothing being left of her body besides a part of her skull, a small clump of dirtied hair, and a piece of cerecloth.

In the 19th century, during the restoration of Sudeley Castle, the Dent family commissioned a marble tomb for Katherine within the newly recreated chapel. It was designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and carved by John Birnie Philip, the same men responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park.

In April of 1861, Katherine would be laid to rest for the final time within the castle. Although it is said she was "shriveled to little brown dust," Katherine was finally allowed to rest in peace.

Beyond Survival: The Queen’s Lasting Legacy

The desecration of Katherine’s grave stands as a stark reminder of how even in death, women have often been subject to exploitation, voyeurism, and historical erasure. Despite her intellect, resilience, and influence, Katherine’s legacy has been reduced to her role as Henry VIII’s sixth wife.

Yet, Katherine's life tells a far more powerful story. She championed religious reform, advocated for higher education, authored profound theological works, and deeply cared for her husbands, stepchildren, and daughter. She governed as regent in the king's absence and helped steer the country. She even evaded a near execution with nothing but friends and her own wit. Her strengths deserve to echo in history.

Though her body was defiled, Katherine's legacy endures. She remains one of the most influential queens in English history due to her accomplishments and is among the most remarkable women. We can only hope that Katherine's legacy remains this way, untarnished against the tests of time.

Bibliography

Foxe, John. Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Published by John Foxe, 1563.

Fraser, Antonia. The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1992.

Historic Royal Palaces. “Katherine Parr: Scholar, Stepmother, Survivor.” Accessed February 23, 2025. https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/history-and-stories/katherine-parr/

History Calling, "CATHERINE PARR'S burial and SHOCKING CORPSE MUTILATION | First Protestant funeral for English royalty", December 10th, 2021, educational video, 22:34, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6lPB4uzmwI

Horenbout, Lucas (Attributed), Miniature of Katherine Parr, c. 1544. Watercolour on vellum. Sudeley Castle.

Lucky, Ashton. Prayers and Meditations Full Book. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Lucky, Ashton. Katherine Parr's Tomb. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Lucky, Ashton. Recreation of Katherine Parr's Tomb Inscription. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Lucky, Ashton. Katherine Parr Grave Robberies. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Lucky, Ashton. Katherine Parr Locket. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Lucky, Ashton. Exterior of Sudeley Castle. Digital photograph. March 2025.

Master John (Attributed), Katherine Parr, ca. 1545. Oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery.

Master John (Attributed), Portrait of Katherine Parr, ca. undated. Oil on panel. Sotheby's.

Neville, Margaret. Will of Margaret Neville. Published by Margaret Neville, 1546.

Parr, Katherine. Psalms or Prayers. Printed by Thomas Berthelet, 1544.

Parr, Katherine. Prayers and Meditations. Published by Katherine Parr, 1545.

Parr, Katherine. Lamentations of a Sinner. Published by Katherine Parr, 1547.

Parr, Katherine. Letter to Princess Mary. Published by Katherine Parr, 1544.

Parr, Katherine. Letter from Katherine Parr to Lord Thomas Seymour. Published by Katherine Parr, 1547.

Parr, Katherine. Letter from Katherine Parr, the Queen Dowager, to her husband, Lord Seymour of Sudeley. Published by Katherine Parr, 1547 or 1548.

Parr, Katherine. Queen Katherine Parr's Letter to Sir Thomas Seymour. Published by Katherine Parr, 1547.

Prince Edward VI. Prince Edward to Queen Catherine. Published by Prince Edward, 1546.

Prince Edward VI. Edward VI to Katherine Parr. Published by Prince Edward, 1547.

Unknown. KP open book. Digital photograph. Unknown.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this Study Abroad class was provided by the UAH Honors College.

Additional funding provided by my incredible parents, without whom I could not have done this project.

I would like to thank Reagan Grimsley for his dedication to teaching the course.

Finally, I would like to give a special thanks to archivist Derek Maddock at Sudeley Castle for granting access to archival records and sharing his expertise on Tudor history.