Maude Valérie White During the British Musical Renaissance

Hannah Kelley, Spring 2025

The British Musical Renaissance was a period of artistic revitalization in the United Kingdom from the 1880s to the late 1910s. During this era, English music experienced considerable development and a strengthened sense of national identity. Several influential composers emerged, including Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Edward Elgar, who became leading figures in the movement. However, while male composers thrived, female composers were frequently disregarded, with their contributions marginalized or undervalued. Despite these obstacles, some women built successful musical careers. Maude Valérie White was one of the few female composers to transcend these barriers, tailoring her compositions to commercial demands while preserving her creative integrity.

Maude Valérie White was a British composer and pianist recognized for her contributions to the art song and vocal music of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1855, she began studying piano at the age of seven. She attended several conservatories, including the Royal Academy of Music, where she became the first woman to earn the prestigious Mendelssohn Scholarship. Throughout her career, she was inspired by Italian opera, Romantic stylistic trends, and her extensive travels. She frequently set her music to texts in various languages—which she translated herself—enabling her to reach diverse audiences. White’s music gained acclaim in Britain and continental Europe, and she regularly performed her own works, showcasing her rare combination of performance and compositional prowess. Though her talents rivaled those of Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Elgar, she received significantly less recognition, primarily due to the prevailing gender prejudices of her time.

White’s career was profoundly influenced by the gender inequities of her era, which restricted her recognition and professional prospects despite her substantial abilities. One notable example occurred during her 1883 visit to Vienna, where she studied under Robert Fuchs, a composer and conductor at the Vienna Conservatory. In her memoir Friends and Memories, White recalls that Fuchs “strongly advised” her to pursue instrumental music in addition to or instead of piano and vocal works (264). Instrumental music was gaining prestige, yet White found it challenging to compose in this genre, later confessing that her perceived shortcomings led to depression (Friends and Memories 264). While her struggles with instrumental composition were partly individual, they were also shaped by the gendered norms of the period. Instrumental music was viewed as a more serious, elite domain dominated by men, whereas women were steered toward vocal music and art songs, deemed more appropriate to their assumed emotional and domestic sensibilities. White’s difficulties reflect not only a personal hurdle but a systemic obstruction that hindered women’s full participation in certain musical spheres.

Elsewhere in her memoir, White recounts a conversation with Alberto Randegger, who remarked on the intricacy of her compositions. He noted that while musicians admired the sophistication of her music, publishers frequently insisted on simplifying it to appeal to a wider audience, which he referred to as the “real public” (Friends and Memories 184-185). This tension between artistic vision and commercial feasibility was a challenge many composers faced, regardless of gender. However, for women, these demands were often intensified by the belief that their music should be delicate, uncomplicated, and suitable for amateur musicians. As Dr. Sophie Fuller highlights in her dissertation on women in music during the British Musical Renaissance, publishers and critics routinely reinforced these assumptions, making it difficult for female composers to earn recognition for more ambitious works (123-125). While male composers also encountered market pressures, they generally had greater liberty to resist without endangering their careers. White’s concessions demonstrate how commercial forces shaped her output, curbing the extent to which she could fully realize her artistic aspirations. These constraints perpetuated the disparities that prevented female composers from attaining equal status with their male peers during the British Musical Renaissance.

White’s music is distinguished by its lyrical expressiveness, attentive text setting, and lush harmonies informed by Romantic traditions. As a composer of art songs, she emphasized the interplay between melody and poetry, often selecting texts that deepened the emotional resonance of her compositions and employing word painting. Her ability to translate lyrics from multiple languages allowed her to connect with a broader audience, extending her reach beyond English-speaking listeners. Her encounters with Italian opera and continental musical traditions were instrumental in shaping her compositional voice. Works such as Two Love Songs, Pictures from Abroad, and Three Little Songs highlight her musical sensibilities and reveal where she may have simplified her style to accommodate commercial preferences.

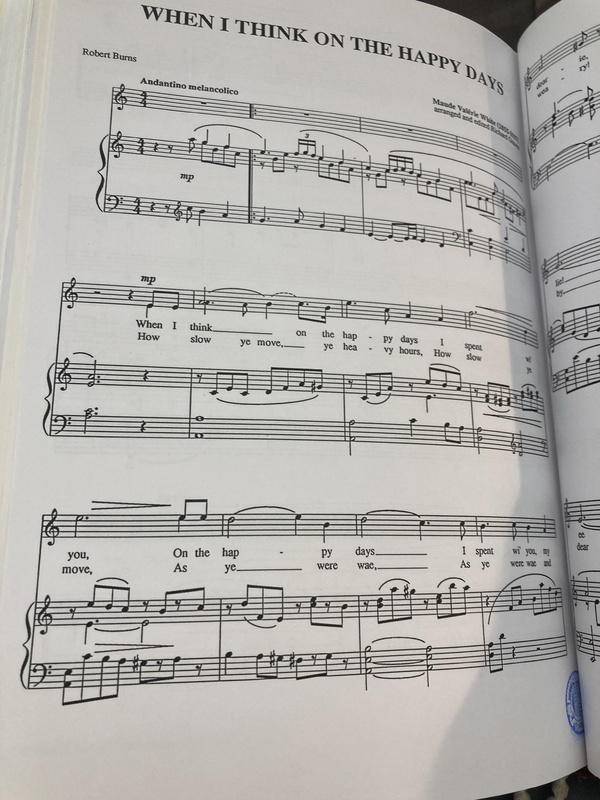

This equilibrium between creative expression and accessibility is apparent in Two Love Songs, where White fuses lyrical melodies with piano accompaniments that support the emotional impact of the text. Both movements—“A Youth Once Loved a Maiden” and “When I Think on the Happy Days”—are art songs set to 18th-century poetry. The first movement–in A harmonic minor– suggests separation between the titular youth and maiden. Its accompaniment is straightforward, featuring mostly whole, half, and quarter notes, with minimal accidentals beyond the characteristic raised seventh. Combined with its moderate andantino tempo, the first movement is notably less intricate than the second. The second movement, also in A harmonic minor, includes more accidentals and a complex melodic structure. It introduces a more rhythmically demanding accompaniment with sixteenth notes and sixteenth-note triplets. The left hand features runs spanning over an octave and jumps into the treble range. Although these elements are not particularly difficult—especially at the slower andantino melancolico tempo—they require greater precision than the first movement. Overall, Two Love Songs is relatively accessible, particularly when compared to White’s more advanced works.

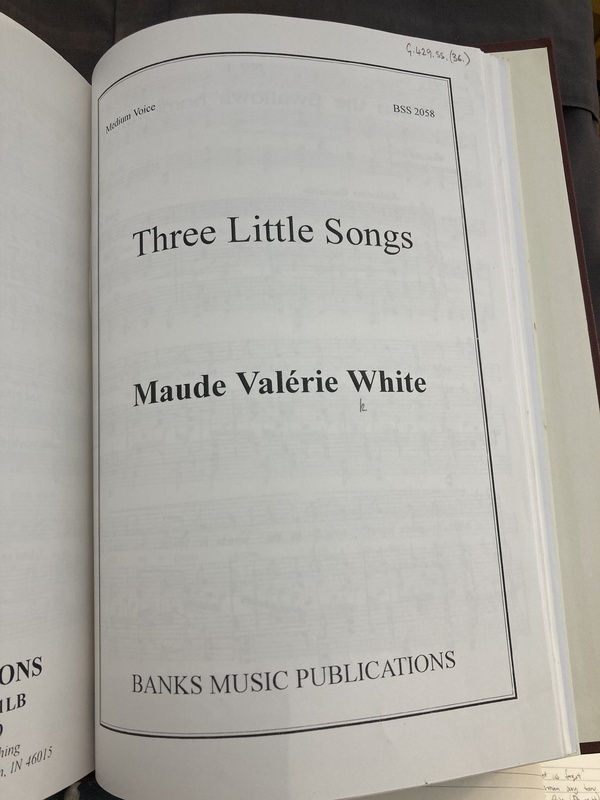

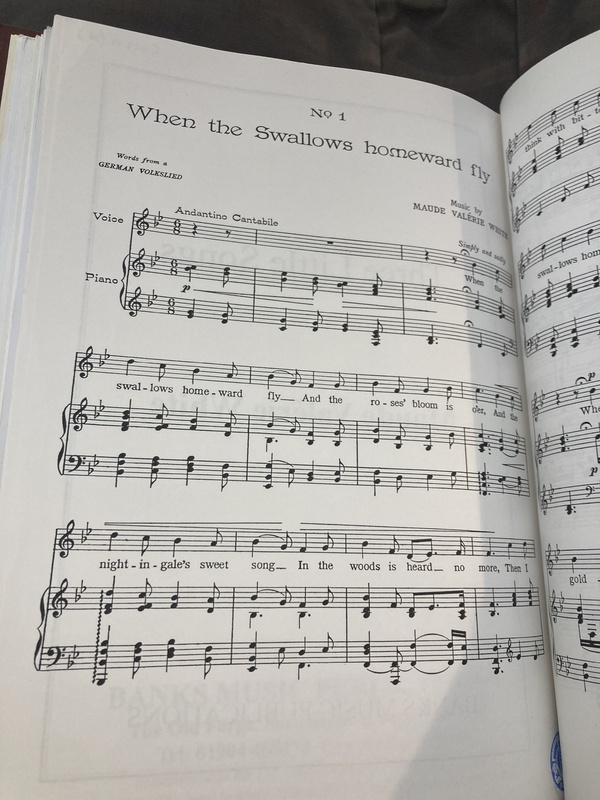

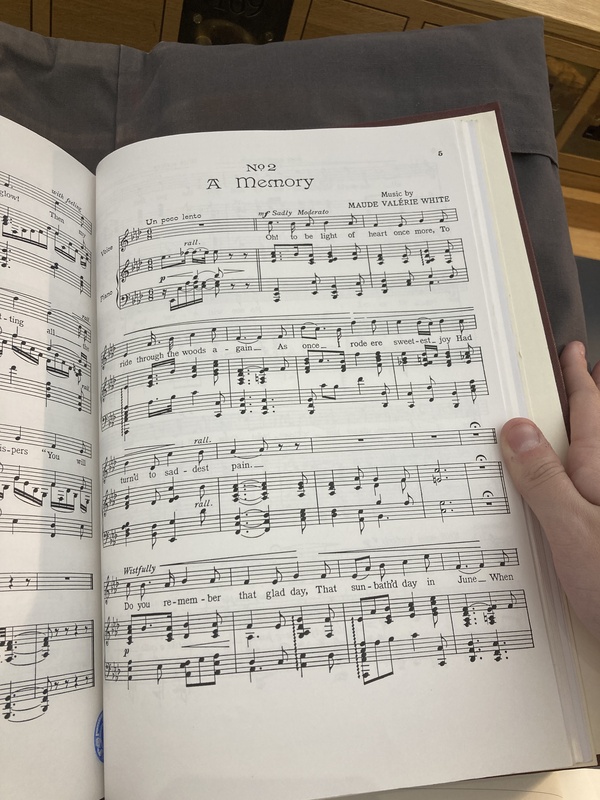

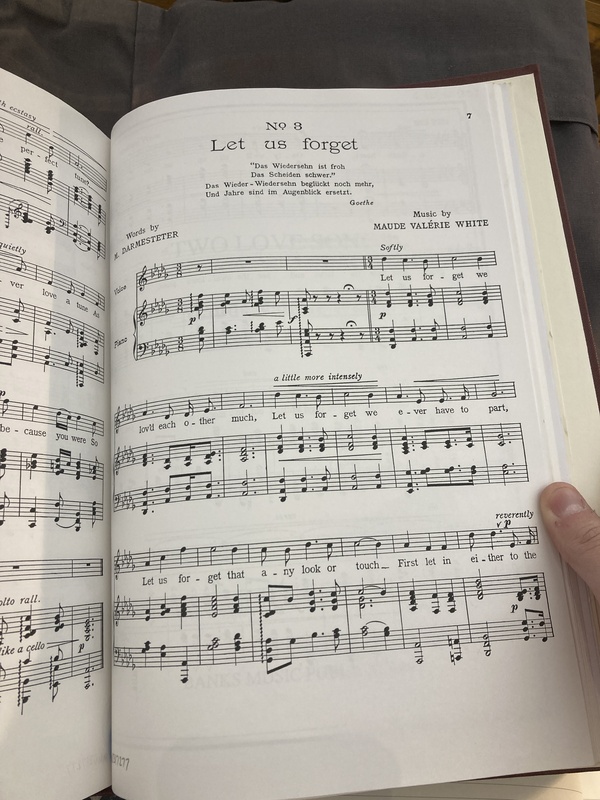

Three Little Songs represents a more sophisticated example. The three movements—“No. 1 When the Swallows Homeward Fly,” “No. 2 A Memory,” and “No. 3 Let Us Forget”—draw from the German Volkslied and the poetry of Arsène Darmesteter. The first movement, in G minor and 6/8 time, conveys increased complexity through rolled chords, 32nd notes, and intricate right-hand figures. With its andantino cantabile tempo, the movement blends moderate pacing with detailed articulation. The second movement, also in 6/8 and marked un poco lento, introduces additional accidentals, rolled chords, and grace notes, albeit mitigated by its slow tempo. The third movement lacks a tempo indication, inviting interpretative flexibility. Though rhythmically simple, it shifts from 3/8 in the introduction to 3/4 in the body and includes syncopated sixteenth-note passages. Overall, Three Little Songs is more challenging than Two Love Songs, though both are still relatively modest compared to other works of the period.

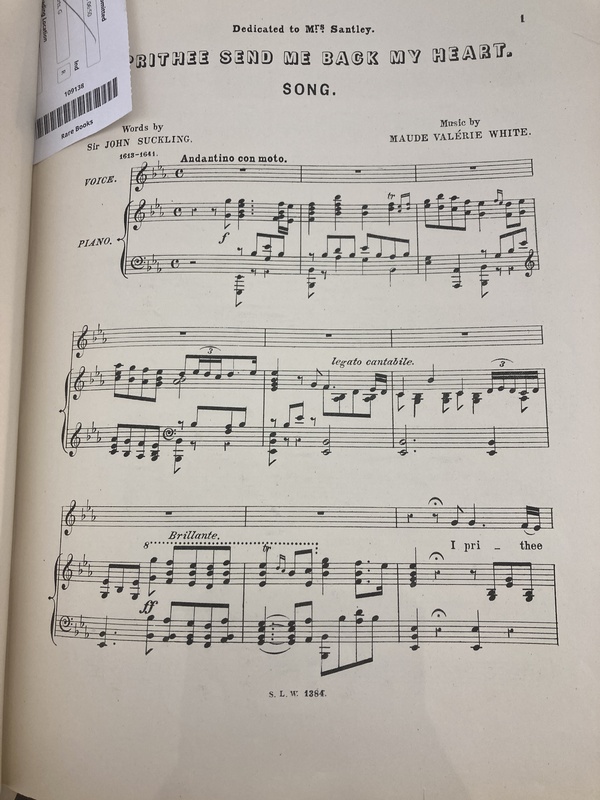

White’s earlier piece, I Prithee Send Me Back My Heart, demonstrates a markedly higher degree of technical and artistic sophistication. Composed in 1880 with lyrics by Sir John Suckling, the piece spans nine pages—substantially longer than her later, shorter works. From its opening measures, the piece features 32nd-note triplets, wide leaps across clefs, and nuanced tempo shifts. It continues with virtuosic elements such as tremolos, octave passages, and frequent meter changes. Composed while she was a student at the Royal Academy, the piece exemplifies the advanced musicality that earned her the Mendelssohn Scholarship. Compared to her later compositions, I Prithee Send Me Back My Heart showcases White’s early foray into complex compositional techniques and her ability to merge technical command with emotional nuance.

This disparity in complexity suggests that White deliberately modified her musical style to align with commercial realities. As her reputation grew, her works became more accessible and less technically demanding. White’s evolution toward simplification was likely a calculated effort to navigate the male-dominated marketplace. By focusing on shorter, more marketable pieces, she expanded her appeal to publishers and amateur musicians alike, increasing her visibility and success. In contrast to her later works, I Prithee Send Me Back My Heart underscores her initial artistic ambition and illustrates how industry pressures likely compelled her to streamline her style to remain relevant.

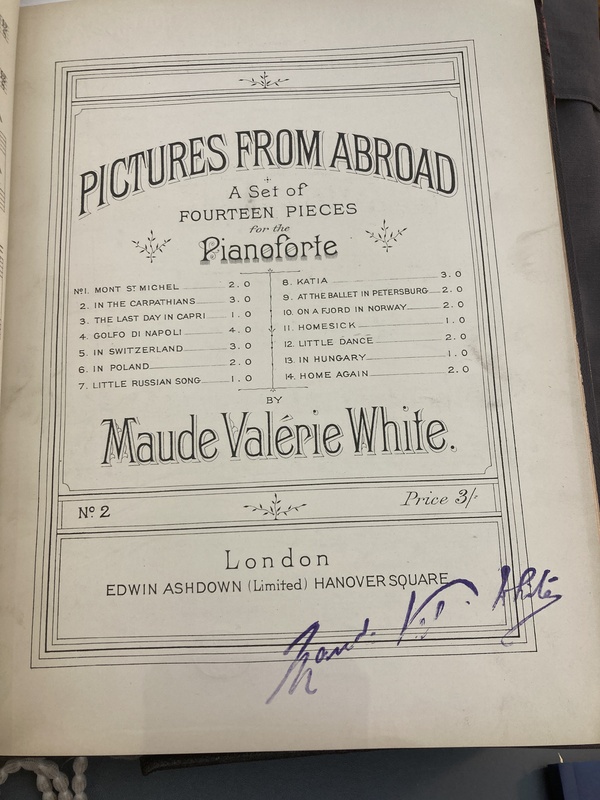

Beyond simplification, White also composed leveled educational pieces to reach a broader audience of learners. One such example is Pictures from Abroad, a collection of fourteen piano pieces organized by difficulty from an arbitrary level one to level four. These pieces vary in complexity, from basic melodies with simple accompaniment to rhythmically and harmonically sophisticated works. Beginner-level pieces employ elementary rhythms and hand positions, while more advanced selections include accidentals, dynamic variations, and expressive phrasing. This tiered structure made the collection useful for educational purposes and enhanced its marketability to teachers and students. Like her simplified art songs, this educational approach demonstrates White’s ability to adapt her music for widespread appeal while maintaining artistic merit.

Maude Valérie White’s career embodies the compromises and challenges female composers faced during the British Musical Renaissance. While her early compositions reveal technical mastery, her later works reflect a purposeful turn toward accessibility shaped by social expectations and commercial pressures. Through simplified art songs and educational collections like Pictures from Abroad, White reached larger audiences without compromising musical quality. Her adaptability in the face of systemic limitations highlights the resilience required of women in music, making her legacy all the more noteworthy.

Bibliography

Ellis, Alfred. Maude Valérie White, from a 1901 publication. February 1901. Lady’s Realm, “Some Lady Songwriters”, p. 475.

Fuller, Sophie. “Women Composers during the British Musical Renaissance, 1880-1918.” Women Composers during the British Musical Renaissance, 1880-1918. 1998. King’s College University of London, PhD dissertation.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of A Youth Once Loved a Maiden. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Friends and Memories Dedication. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of I Prithee Send Me Back My Heart. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Pictures from Abroad Title Page. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Three Little Songs No. 1. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Three Little Songs No. 2. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Three Little Songs No. 3. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Three Little Songs Title Page. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of Two Love Songs Title Page. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

Kelley, Hannah. Picture of When I Think on Happy Days. 12 March 2025. Author’s personal collection.

White, Maude Valérie. Friends and Memories. Edward Arnold, 1914.

White, Maude Valérie. I Prithee Send Me Back My Heart. Canzonet, Words by Sir J. Suckling. 1880.

White, Maude Valérie. Three Little Songs : Medium Voice. Banks Music Publications, 1995.

White, Maude Valérie. Two Love Songs : Medium Voice. Banks Music Publications, 1993.

White, Maude Valérie. Pictures from abroad : a set of fourteen pieces for the pianoforte. Edwin Ashdown, 1892.