Black Arrow - How a Country Loses Orbital Rocketry Capability

Ethan Burks, Spring 2024

How does a country have, then lose, their homegrown orbital rocketry capabilities? There have been over a dozen countries to create orbital rockets, then fly them successfully, but only one completely removed itself from any space ventures following a successful orbital vehicle: The United Kingdom. The UK launched the Black Arrow vehicle four times, but canceled the program even before its greatest success: launching the Prospero satellite into Low Earth Orbit.

NASA was extremely interested in the Black Arrow vehicle, as launching from Australia offered a wider range of opportunities to launch into different orbits than was possible in the United States, but despite the British program’s enthusiasm for NASA money and support, Parliament never gave them the chance to take advantage of it.

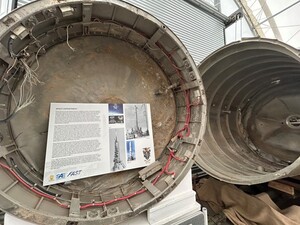

Black Arrow is an interesting vehicle. As with many vehicles of the time, it was built off the back of a ballistic missile, this one being the Black Knight suborbital vehicle. It launched a total of four times, two successes, and two failures. The first launch occurred in 1969, with the R0 vehicle (apparently they followed the Python naming scheme!), which was launched without a payload or a third stage. The first stage suffered a thrust vector control failure, and began to spin out of control due to an electrical fault in the first stage’s engine. Just over a minute into flight, safety teams were forced to detonate the Range Safety Ordinance and blow the rocket into bits. This was not an uncommon failure for early rockets, especially those with complex engines, as the Gamma-304 Type-8 was. The R1 vehicle would have to replicate the same profile; initially slated to perform the first orbital launch, scientists were unwilling to trust their payload to an unflown second stage. The R1 vehicle performed flawlessly when it launched a year later, in 1970, and both stages burned to completion.

Upon completion of the suborbital test flight, the go-ahead was given to the teams to mate a payload, named X-2/Orba, and mate a fully-functioning Waxwing third stage. However, the R2 vehicle’s second stage suffered from a failure, leading to a premature shutdown of the Gamma-304 Type-2 engine about 13 seconds early. While the Waxwing fired perfectly, the Orba satellite was still left under orbital velocity. This failure put the program’s shortcomings squarely in the sights of Parliament, and just months after the failure of R2 in September of 1970, the Black Arrow program was on the chopping block. Sure enough, before the program even had an opportunity to redeem itself, it would be canceled by Parliament in July of 1971. Luckily for the teams, the completed R3 vehicle had already been shipped to Australia, and for that reason – and that reason alone – they were allowed to have one last attempt to place Britain’s first satellite, dubbed the X-3/Prospero, into orbit.

R3 worked flawlessly. Powered into orbit in around 10 minutes’ time, Prospero became the first British satellite launched by a British vehicle to enter orbit. Prospero, and presumably its Waxwing upper stage though I couldn’t find anything to confirm this, still remain in orbit to this day. Prospero would be fully operational for only around 2 years, as its tape recorder suffered an electrical fault following a Coronal Mass Ejection. Its radio chirps could be heard by amateur radio operators until at least 2004, though, as found by a BBC show. There is still a chance that we could still hear the chirps from Prospero today, though it is likely being drowned out by other traffic.

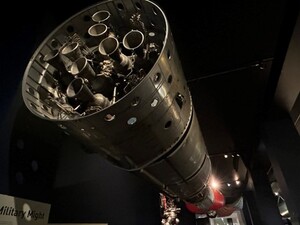

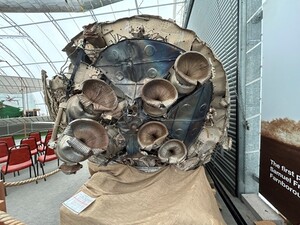

I was blessed with not one, but two excellent opportunities to learn more about the Black Arrow: the Science Museum in London, home to the unflown R4 vehicle, and the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, home to the flight-used R3 first stage, recovered from the Australian Outback some years after its flight. What I discovered, though, was that even the British have largely forgotten their own history of spaceflight. There was shockingly little material on the R4 vehicle, despite being fully intact; just a single panel of information, and the vehicle itself swung overhead, seemingly longing for someone to notice it.

Parliament, and the UK space program, had received very little interest in the Black Arrow vehicle commercially, and canceled it despite a looming deal with NASA for a ride-swap agreement between Black Arrow and NASA’s Scout launcher, a similarly capable vehicle. Scout flew until the early 1990s, while Black Arrow, very much its equal, was canceled over 20 years before, and the ride-swap deal would obviously fall through as a result of the cancellation. Britain themselves would build just one more satellite in its series, the X-4, launched aboard a Scout, but then that satellite series too would be canceled. Ah, budget cuts, the bane of all things spaceflight related…

Black Arrow had aspirations not just inside the UK, but outside of it, too. Its launch was a major collaboration between the UK and Australian governments, occurring from a site in Woomera, and the Woomera launch facilities have since largely sat vacant, as the UK never returned with a launch vehicle. Additionally, while countries like the US and USSR celebrated their space ventures, the UK (and to a lesser extent, France) rarely discussed such things; seeing them as merely military matters, and removing them from the public eye, cursing them to a life and legacy of obscurity. Something long noticed by British rocketry experts and enthusiasts is that when students go to places like the London Science Museum, they are cruelly unaware that their own country ever went to orbit, as it’s but a footnote in the majestic history of space exploration.

But what if things had been different? Before the cancellation of the program, there were already plans to build at least one more Black Arrow, designated R5, of a current design, but beyond that was theorized a massive upgrade that would’ve placed Black Arrow solidly in the small launch market, boosting the payload capacity further into a market that even today is only serviced by a select few providers – primarily Rocket Lab’s Electron vehicle.

Even further down the line were theorized liquid hydrogen upper stages for a more powerful Black Arrow successor. This potential upgrade, though, likely never would have made it off the drawing board without heavy support from both the UK and Australian governments, as launching from the hot Australian outback is rather painful for launching anything with liquid hydrogen, but it would have put British rockets likely on par with the venerable Atlas vehicle that NASA used heavily.

Would Black Arrow have survived, had it lasted into the era of commercial satellites that prospered just a few years later, truly beginning in the early 1980s? Well, we will never know for certain. I feel that it would have thrived in that era, as early commercial satellite providers likely could have taken advantage of the Black Arrow to place satellites into highly inclined orbits to be able to provide communications in places like Britain, but instead those satellites would be forced to launch aboard the Atlas vehicle. Perhaps Black Arrow was doomed to fail, alas. But it was an idea, a brilliant idea, perhaps one ahead of its time. It truly is a shame that its own people have forgotten about it.

Bibliography

Allen, John, The Black Arrow Rocket: A History of a Satellite Launch Vehicle and its Engines: Douglas Millard; Science Museum/Gazelle, Lancaster, 2001, Space Policy, Volume 18, Issue 2, 2002, pp.167-168

Amos, Jonathan. “Plans for UK Satellite Launcher.” BBC News, BBC, 3 Feb. 2009, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7862827.stm

Buchholz, Katharina. "The Countries Capable of Launching Space Rockets." Statista, Statista Inc., 18 Jul 2022, https://www.statista.com/chart/27792/countries-capable-of-launching-space-rockets/

Hill, C. N. (2001). A Vertical Empire: The History of Britain’s Space Programme (1st ed.) Imperial College Press

Millard, D. (2001). The Black Arrow Rocket: A History of a Satellite Launch Vehicle and its Engines. Science Museum.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the Honors College for setting up a wonderful trip, and to our professors (and Mrs. Gracie Jeffers from the International Studies office!) for a wonderful class. It wouldn't have been possible without you all. Thank you to Reagan Grimsley and Charlie Gibbons for teaching this class and leading us on our little escapade to another country. Still bummed you didn't get to go with us, Charlie. Here's hoping that next time (because there will be a next time!) you get to go!

A second professional thank you to the curators and staff, especially Curator Graham Rood, of the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, better known as FAST, for letting me use the photos of the first stage of the R3 vehicle in my research. Thank you for a wonderful tour of your museum and an enthusiastic approval of my request, in addition to offering me a space in your own archives. I hope that I've lived up to your expectations!

On two more personal notes, the first is a thank you to the staff of the Salmon Library for enabling my research and continuing to get sources delivered to me right up to the end of the semester.

Last, but certainly not least, a thank you to my parents, who have long encouraged my twin loves of space and history -- even if you didn't have any conscious effect on my choice of topic for my research, without your long-term support of my love for spaceflight (and financial support for college!) I wouldn't have been able to conduct this research.