Huntsville at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century

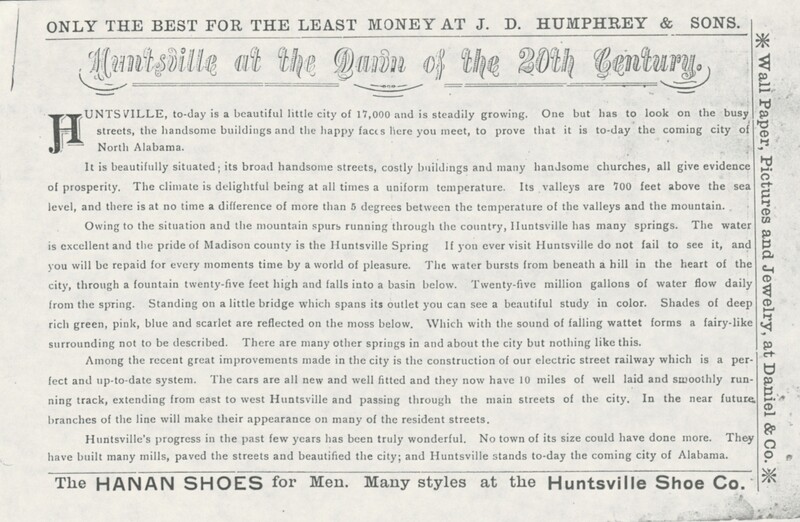

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the financial interests of Huntsville’s progressive businessmen led a small group of men to control all aspects of development in the city. Huntsville men and women had different approaches to Progressivism and how to advance and uplift Huntsville society. Local businessmen sought to progress Huntsville into the twentieth century through prosperous industry and expansion of business opportunities. Huntsville women sought to improve the quality of life for Huntsville's poorest people and embodied the uplifting society aspect of Progressivism. Huntsville's promotional booklets, pamphlets, and newspapers from the first decade of the twentieth century, such as the 1901 Huntsville Postal and Souvenir Guide, praise the city's progressive businessmen for their “interest in the welfare of the city” and “concern in anything that benefits the future prosperity of Huntsville.”[1] These promotional materials gave a beautiful description of Huntsville, boasted the health benefits of Monte Sano Mountain air and Big Spring, listed advertisements for local businesses and organizations, and praised the work of the city council and the Chamber of Commerce.

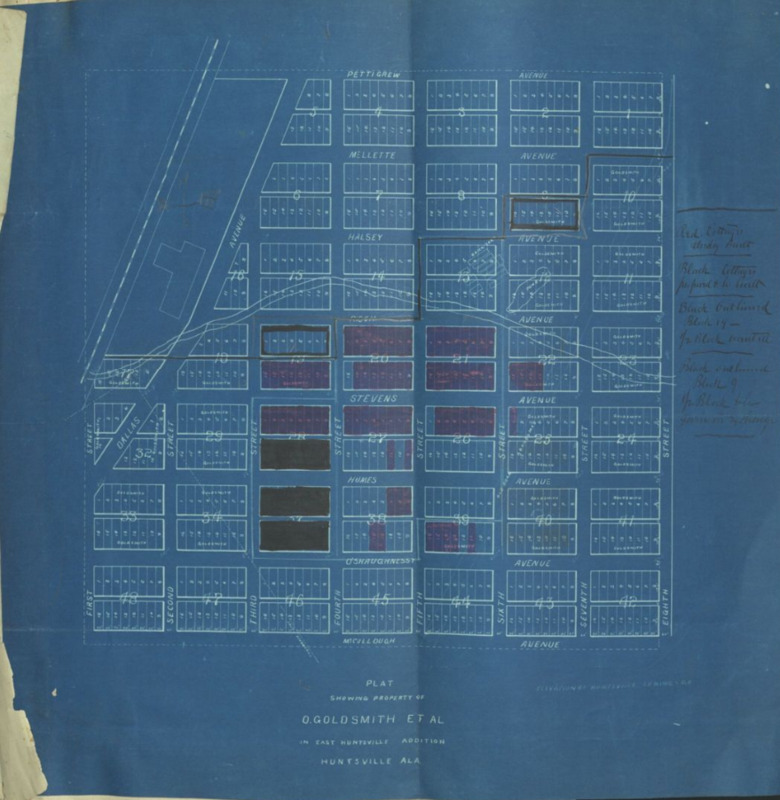

The men of the Chamber of Commerce had business interests in banking, real estate, and the consumer economy. The men of Huntsville's Chamber of Commerce invested their money and energy in promoting Huntsville as a growing, modernizing, industrial city. They attracted and invested in new industry, especially textile manufacturing. The cotton textile industry boom in Huntsville in the 1890s and 1900s bringing with it a growing population of working-class individuals. The same men who invested their time and money in local government and cotton mills also invested in housing and public transportation. In 1900, the Huntsville Chamber of Commerce was led by Tracy Pratt, president; Oscar Goldsmith, vice-president; H.J. Lowenthal, treasurer; and N.F. Thompson, secretary. Each of these men had ties to the cotton mill industry, transportation, housing, and the commercial economy. Tracy Pratt, originally from South Dakota, immigrated to Huntsville to invest in the cotton mill industry and quickly became a city leader and invested almost all the necessary capital for the Huntsville Electric Streetcar and significant capital and leadership in the Merrimack Mill. Oscar Goldsmith was the treasurer of the Dallas Mill and the president of the Huntsville Land Company trusted with managing the construction of the Dallas mill village. Oscar Goldsmith also owned a men’s wear shop in Huntsville and operated a store in the Dallas Mill Village. N.F. Thompson owned Thompson Land and Improvement company which built suburban homes in the East Huntsville Addition.

Beginning in 1886, the North Alabama Improvement Company (NAIC) and the Northwestern Land Association (NLA), also made up of local businessmen, invested in regional improvements to housing and industry. The NAIC was founded in 1886 by brothers Michael and James O'Shaughnessy with the purpose of attracting industry and investors to Huntsville. In 1888, the NAIC purchased two thousand acres of land, renamed the East Huntsville Addition. The East Huntsville Addition was intended to be Huntsville’s first suburb, but the NAIC failed to sell more than a few plots of land. The NAIC sold a large amount of land for the construction of Dallas Mills and village.

The East Huntsville Addition's suburbian vision was brought back to life in the early twentieth century with the influx of cotton mill workers and new businesses to Huntsville. In 1892, Tracy Pratt and the NLA bought the NAIC and took over the promotional work for the region. With the assistance of northern capitalists’ investments and energy in establishing a profitable textile industry, Huntsville saw an exceptional growth in the construction of cotton mills and villages to accommodate the influx of working-class individuals. By 1901, Huntsville had seven textile mills: Huntsville Cotton Mill, Dallas Mills, West Huntsville Cotton Mill, Lowe Mill, Rowe Mill, Madison Spinning Mill, and Merrimack Manufacturing Company, each producing specific textile products. Merrimack, was the product of Tracy Pratt's devotion to securing a partnership with Merrimack Manufacturing Company in Lowell, Massachusetts, the largest textile manufacturing city in the United States at the time. Tracy Pratt sought to make Huntsville the "Lowell of the South."[2] Huntsville newspapers praised the work of Tracy Pratt and chronicled his every move from when he left for trips “to the East in the interest of bringing new industries,” to his grand announcement for the Merrimack mill on July 4th, 1899.[3] Tracy Pratt's involvement in the NLA, the Chamber of Commerce, and other organizations of businessmen made him an integral part of improvement in the city.

To recruit workers to move to Huntsville and work in the mills, Huntsville businessman boasted about the improvements in housing and the overall enjoyability of life in Huntsville using promotional booklets such as the one pictured at the top of the page. Mill village, such as Oscar Goldsmith’s Lawrence Village (pictured above), were advertised in these books and local newspapers. A 1908 promotional booklet, sponsored by the Huntsville Business Men’s Club, details the improvements made in Huntsville since the turn of the century and markets the city toward “those who wish to improve their condition, their surroundings, or health.”[4] This booklet advertised Huntsville as a healthy place to live, neither too hot or too cold; an excellent place for summer and winter resorts; and a rapidly growing city, claiming a population of 9,000 in 1900 and a population of 20,000 in 1908.[5] The city of Huntsville used population as a measure of its perceived modernization and when, in the 1900 census, the city claimed 15,000 residents but was only recognized for 9,000, local news stories reflect the disappointment of Huntsvillians for not being given credit for their growth.[6] This difference in perceived population was likely because the large mill villages at Merrimack and Dallas were not incorporated in the city limits until the middle of the century after most of the mills had closed. The promotional material for Huntsville often boasted about the prosperity of cotton mills and about the growing population of mill workers, but the mills remained unincorporated and the villagers on the outskirts of city life.

Huntsville’s cotton mill investors did their research before bringing mills and thousands of workers to Huntsville. Oscar Goldsmith, president of the Huntsville Land Company and in charge of building the Dallas Mill village, was originally from Lawrence, Massachusetts. Lawrence was a large textile town in the late nineteenth century and had a bad reputation for its deplorable working-class living conditions. In Lawrence, the mill villages were in the city, but the mill investors in Huntsville were determined to separate the villages from Huntsville and improve the local perception of mill village life. Village homes were advertised in promotional materials as neat toy houses painted in pretty tints making them seem cleaner than traditional mill homes in the North.[7] The public image of the mill villages was important for the marketing of Huntsville is the 1890s, so when local charitable organizations visited the mill villages and saw the deplorable conditions: overcrowded rooms and homes, diseases such as measles and typhoid, and malnourishment; they took action.

It was the action of Huntsville’s leading women that led to change in the living conditions in the city and mill villages. Alberta C. Taylor, president of The Village Improvement Society, advocated for cleaner streets in the public square, clean water in the Big Spring, and an overall beautification of the city through intentional landscaping of streets and Big Spring Park. United Charities, a collective charitable organization of women, was dedicated to improving the impact of charitable funds to better the living conditions of poor Huntsvillians and mill workers. The organization also founded and operated an infirmary that would later become Huntsville Hospital. The women of United Charities, such as Mrs. Oscar Goldsmith, visited sick families in the Dallas and West Huntsville mill villages and made the conditions of mill life known to the Huntsville community. City leaders, including Tracy Pratt, owner of the West Huntsville Cotton Mill, did not like the publicity for unsanitary housing and disease as it was a poor advertisement for the city. The women of United Charities and Alberta C. Taylor continued to lobby city leaders and mill managers to improve conditions for villagers.[8]

In September 1900, T.B. Dallas announced several improvements being made in the mill village in partnership with United Charities. Alberta C. Taylor and Anna B. Robertson of United Charities travelled to Nashville to tour the day nursery at the Dallas Mill there. The day nursery was intended to decrease the number of children working in the mill and relieve the mill’s female workers from the added task of watching their children while working in the mill. Dallas also announced plans for a dormitory for “unprotected and homeless girls who work in the mill” and a public-school building. Each of these new buildings were constructed on “the grove” a property north of the Dallas Mill Village formally owned by W.H. Moore.[9]

Footnotes

[1] “Postal Guide & Souvenir, 1901,” 1 January 1901, Frances Cabaniss Roberts Collection, UAH ASCDI, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL. http://libarchstor2.uah.edu/digitalcollections/items/show/14861

[2] Terri L. French, Huntsville Textile Mills and Villages: Linthead Legacy (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017) 59-60.

[3] Huntsville Weekly Democrat, June 6, 1899; and July 5, 1899.

[4] “Huntsville Promotional Booklet,” 1908, Frances Cabaniss Roberts Collection, UAH ASCDI, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL. http://libarchstor2.uah.edu/digitalcollections/items/show/8033

[5] “Huntsville Promotional Booklet,” 1908.

[6] Huntsville Weekly Democrat, October 21, 1900.

[7] Illustrated City of Huntsville,” 1905, Frances Cabaniss Roberts Collection, UAH ASCDI, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL.http://libarchstor2.uah.edu/digitalcollections/items/show/7966

[8] Elizabeth Humes Chapman, Changing Huntsville, 1890-1899 (1932; reis. Huntsville: Historic Huntsville Foundation Inc., 1989) 75-81.

[9] Huntsville Weekly Democrat, September 19, 1900.

References

French, Terri. L. Huntsville Textile Mills and Villages: Linthead Legacy. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017.

Huntsville History Collection. “Betty Berstein Goldsmith.” Accessed October 29, 2024, https://huntsvillehistorycollection.org/hhc/browseperson.php?a=person&pe=Betty%20Bernstein%20Goldsmith.

Rohr, Nancy. “The O’Shaughnessy Legacy in Huntsville.” Huntsville Historical Review 21, no.2 (1994): 1-18. https://louis.uah.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1295&context=huntsvillehistorical-review

Snow, Whitney A. “Cotton Mill City: The Huntsville Textile Industry, 1880-1989.” The Alabama Review 63, no.4 (2010): 243-281.