Cotton Mill Workers as Consumers

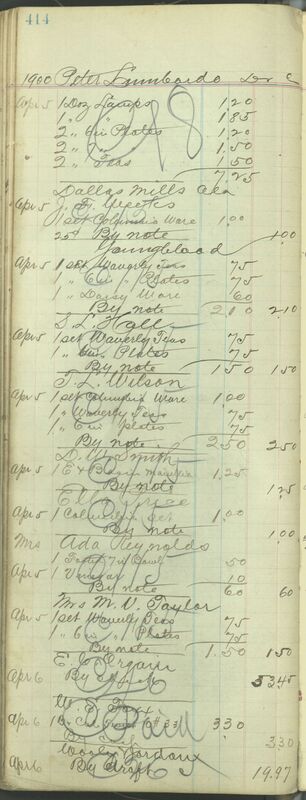

On April 5, 1900, customer J.F. Weeks was the first mill worker customer to purchase items from Harrison Brothers. In Daybook 2, “Dallas Mills Ala” was written above Weeks’ name as the Harrison Brothers often did if the origin of the customer was interesting or if the customer did not have an account with a listed home city. Seven mill workers arrived at the store with J.F. Weeks and were all placed on the same customer account page, 115. Harrison Brothers only assigned one, maybe two customers to a page and it usually was not on the same day. On April 6, more mill workers, all women, arrived, this time identified as being from “Risons Ave.” and “Stephens Ave.” which were streets in the Dallas Mill Village. These customers were also added to account page 115. Page 115, assigned to the first twelve mill workers was removed from Customer Account Ledger 1 and mill workers that appear later in the ledger can be identified by a new notation, “##”, to note that the customer paid in full and was not assigned a credit account.[1]

Among the twelve identifiable mill workers from April fifth and sixth, eight of them were women and eleven of them paid “By note”.[2] It is unclear from the account books whether “By note” refers to some type of Dallas Mill company credit, as some mill workers were often paid with, or if “note” refers to another payment method, such as an early bank paper “note.” Either way, the note was likely associated with some form of credit to the local mills. The arrival of mill workers forced the Harrison Brothers to change their account practices to meet the needs of the customers, but the mill workers were also just what the store needed to advance their Queensware business. Harrison Brothers Tobacco gave each new customer, mostly male middle- and upper-class customers, a credit account, but the store did not instill the same trust in the mill workers. The Harrison Brothers made significantly more money selling Queensware than tobacco because the cheap products, from $0.05 to $0.50 an item, were accessible and desirable. By the end of 1901 the brothers planned to expand the store into two storefronts. Whether the brothers switched to Queensware to attract mill workers, or the products just happened to attract them, either way the store benefited from the new customers.

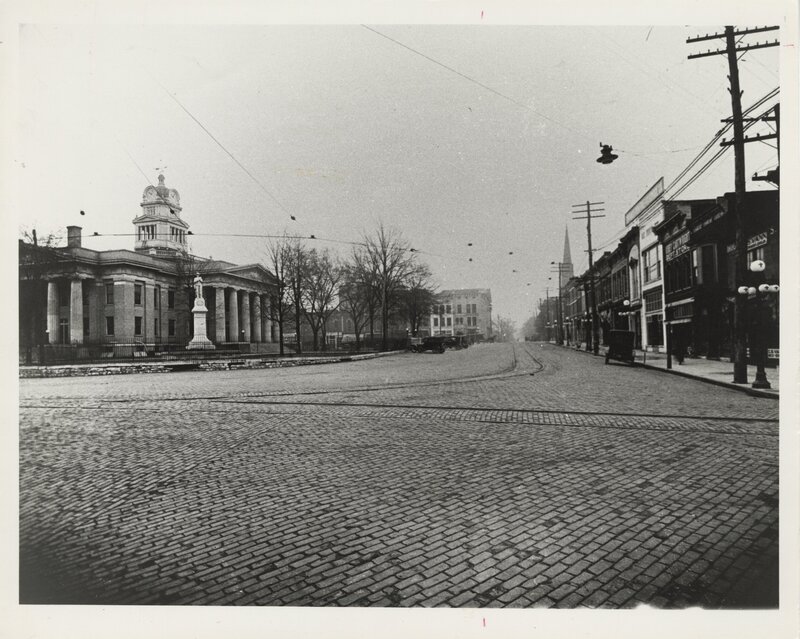

It is not a coincidence that Harrison Brothers decided to switch to selling Queensware in March 1900. In the same month, other stores in Huntsville were also changing their products and marketing. In March 1900, one furniture store advertisement in the Huntsville Weekly Democrat began marketing “FURNITURE CHEAP FOR CASH.” [3] Cheap manufactured furniture, like Queensware, was among the mass-manufactured products that began selling in the South at the beginning of the twentieth century. In March 1900, local merchants were preparing for the completion of the first Huntsville electric streetcar, also known as the trolley.

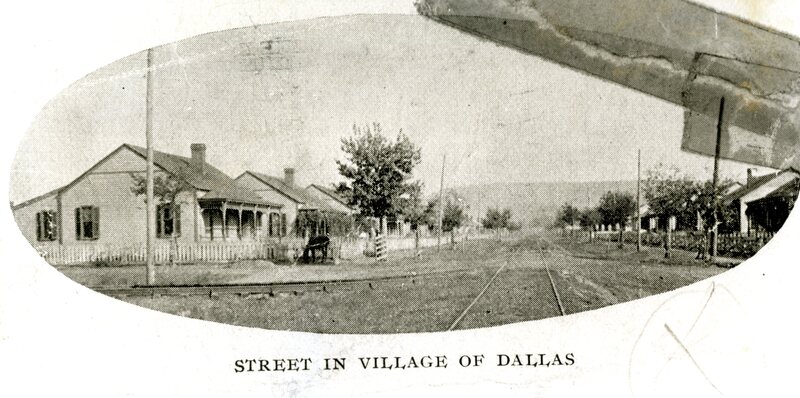

The first trolley tracks were laid from the Dallas and Merrimack Mills to Courthouse Square through Commercial Row. This directly connected downtown to the mill villages and the mill villages downtown. The Dallas Mill Village was a mile and a half away and Merrimack was three miles away from Courthouse Square. This distance could be walked, especially if mill workers could not afford the trolley fare. The Huntsville Weekly Democrat did not report mill workers using the trolley, rather it reported “trolley parties” held by Huntsville’s upper-class to ogle at the mills and mill workers.[4] To the upper class the trolley was another leisurely activity, but to mill workers, the trolley was an opportunity to escape the mill village bubble.

Much of the literature about cotton mills focuses on how mills provide everything for their workers including housing, stores, schools, and healthcare. However, mill workers did shop at Harrison Brothers, the trolley connected the villages to the downtown commercial district, and other businesses changed their marketing to appeal to working class individuals who could only afford cheap manufactured goods and paid in cash or company credit. Huntsville’s mill workers, at the turn of the century, were not confined to the stores that the mills provided, rather they took advantage of the opportunities that Huntsville provided to shop for household goods for their new homes.

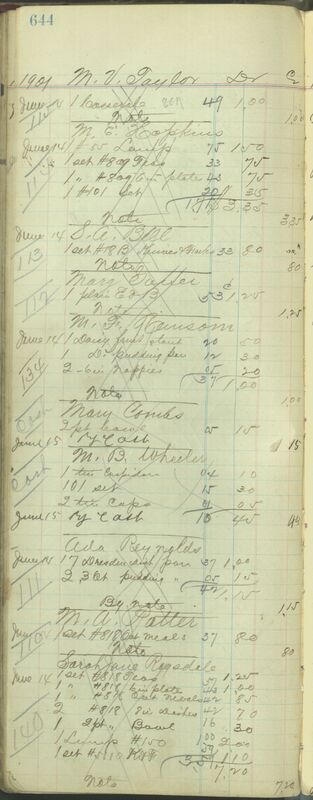

After April 5 and April 6, 1900, mill workers continued to go to Harrison Brothers and made small purchases of Queensware ranging from $0.60 to $2.00. The Harrison Brothers removed page 115 from the Customer Account Ledger and instead used "##" or "#" to identify mill workers in the daybooks. Mill workers can also be identified in later accounts by their unique payment "By note." Mill workers and individuals who made similar small purchases became the primary customers at Harrison Brothers and helped the store recover from the loss of its tobacco consumers. Women, especially mill women who made up a significant number of mill workers, began to overwhelm the store and often shopped in groups. Ada Reynolds and Mrs. M.V. Taylor were two frequent mill worker customers that came to the store with the first wave of mill workers in April 1900. The two women were among the few regular mill customers at Harrison Brothers.[5]

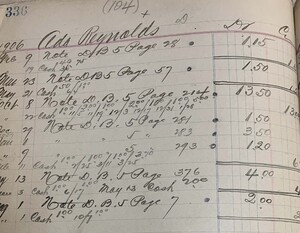

Mill workers from Dallas, Merrimack, and other mills continued to go to Harrison Brothers after 1900 and became the store's primary customers. Mill workers were not initially given credit accounts, and, with the increase in one time purchases at the store, Harrison Brothers stopped giving accounts to every customer, as they had done with their tobacco customers.[6] This decision was likely made because the brothers had more customers to keep track of and because most of their new customers did not have collateral for a credit account. However, the practice of not giving mill workers credit accounts did not continue long. In a 1906-1908 Customer Account Ledger, mill workers are listed on every page. The village locations, such as Dallas, Merrimack, Lincoln, West Huntsville, etc., are noted in pencil by the persons name. On Ada Reynolds's account page, the letter "D" written in pencil above her name stands for Dallas.[7] Beginning in 1900, mill workers were a significant part of Harrison Brothers and influenced the store's expansion of property and products in the following years.

Footnotes

[1] “Daybook 2,” Harrison Brothers Hardware, UAH ASCDI; "Customer Account Ledger 1", Harrison Brothers Hardware, UAH ASCDI.

[2] "Daybook 2," Harrison Brothers Hardware, UAH ASCDI.

[3] Huntsville Weekly Democrat, March 7, 1900.

[4] Huntsville Weekly Democrat, March 7, 1900

[5] "Daybook 2," Harrison Brothers Hardware, UAH ASCDI.

[6] "Customer Account Ledger 1," Harrison Brother Hardware, UAH ASCDI.

References

Cohen, Lizabeth A. “Embellishing a Life of Labor: An Interpretation of the Material Culture of American Working-Class Homes, 1885-1915.” Domestic Ideology and Domestic Work 4, no.2 (1992): 752-775.

French, Terri. L. Huntsville Textile Mills and Villages: Linthead Legacy. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017.

Hubka, Thomas C. How the Working-Class Home Became Modern, 1900-1940. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Marek, Jim. “Did You Know? The Street Car.” Huntsville History Collection. June, 2010. https://huntsvillehistorycollection.org/hhc/showhpg.php?a=article&id=297

Snow, Whitney A. “Cotton Mill City: The Huntsville Textile Industry, 1880-1989.” The Alabama Review 63, no.4 (2010): 243-281.