Called to Care: Faith-Based AIDS Responses in 1980s/1990s Alabama

An RCEU Summer Research Project by Morgon Newquist

"When people are sick and suffering, my faith calls me to respond."

Rev. Malcolm Marler

During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, the response from religious communities varied significantly. While some churches turned their backs on those affected by the disease, driven by fear, misunderstanding, and stigma, many more embraced and supported AIDS patients with compassion and care. Faith-based organizations and congregations played a crucial role in providing personal care, spiritual support, housing, and education.

Research into the early days of the epidemic in Alabama showed that religious people all over the state were ready to jump in to help in whatever way they could, even before their own communities were impacted by the disease.

These sentiments and the willingness to care for the sick in their communities, no matter the illness or way of infection, can be seen across denominations.

In addition to many denominations and churches creating their own programs to respond to the AIDS crisis, religious congregations as a whole worked together. The AIDS Interfaith Network was founded in 1988 as an association of various local AIDS ministries. In 1994, this organization founded the Council of National Religious AIDS Networks as "a better method of talking and planning among those of us involved in religious-based AIDS work." The May meeting of the Network included representatives from Lutheran, Episcopal, Jewish, Unitarian-Universalist, Roman Catholic, United Church of Christ, United Methodist, Presbyterian, Disciples of Christ, and Metropolitan Community Churches, as well as the faith-based and pan-denominational groups AIDS Advocacy in African American Churches and Balm in Gilead, Inc. This same year the Network estimated that there were 3000 faith-based AIDS ministries in the nation.

Faith-based organizations played a vital role in supporting AIDS victims in the 1980s and 1990s. This exhibit underscores the importance of caregiving in addressing public health emergencies, highlighting the essential role of faith-based organizations in Alabama in providing comprehensive support to AIDS patients.

ACTIVISM VS. CAREGIVING MODELS

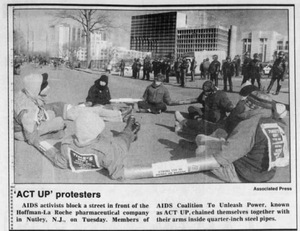

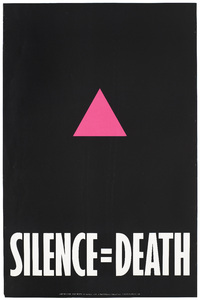

When examining the early days of the AIDS pandemic, two distinct ways of combating the disease become apparent. One is through activism - raising awareness, demanding change, fighting for medical research and equality in the law. The other is a more personal model - making a difference through caring for the individual person affected by AIDS. A tree-based view, versus a forest-based view.

In scholarship about the 1980s and 1990s, there is an emphasis on direct action, public protest, and other aspects of public life, with little attention paid to private life. This emphasis caused much of the caregiving work done to combat HIV/AIDS to pass unnoticed, despite its impact at the time. "Home protects, but also hides," states academic Stephen Vider in his paper "Public Disclosures of Priate Realities". The private aspects of this care - nursing, feeding, housing - have been forgotten in the divide between public and private spaces.

Many activists, including Larry Kramer, founder of the activist organization ACT UP, viewed the care model as unimportant, or even as a distraction standing in the way of progress. He emphasized the need "to get out of the bedroom and into the streets," and dismissed caregiving work as feminine.

As important as activism is, real people still desperately needed care. Ill men, women, and children needed to be taken to the doctor, needed housing, and needed food. Changing the world takes time, no matter how aggressive and eye-catching direct action can be. Recognizing the contributions of care providers and the work done within 'private life' is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the efforts to combat the HIV/AIDS crisis.

This exhibit highlights the overlooked contributions of faith-based organizations in Alabama during the 1980s and 1990s, emphasizing their crucial care-based support for AIDS patients and challenging the historical bias that has predominantly focused on activist efforts and negative religious responses.

FAITH AND AIDS

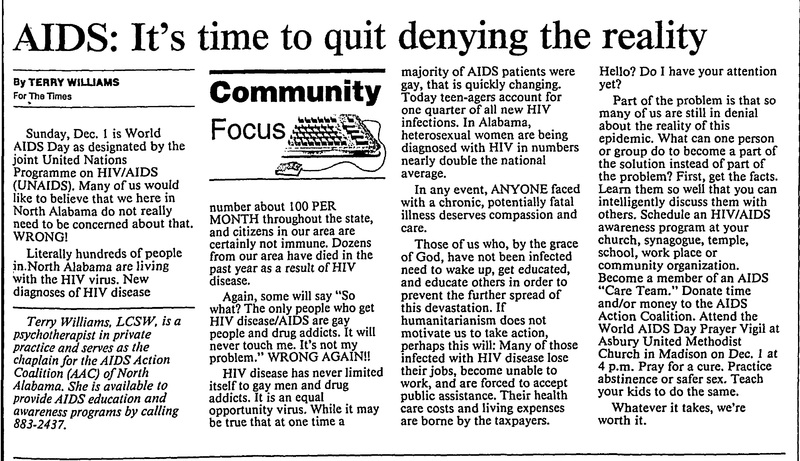

For many faith communities, AIDS presented a tricky problem: because of its association with intravenous drug use and homosexual intercourse, it quickly garnered a public perception as a disease affecting only "immoral" individuals. In addition, many churches did not condone preventive measures such as condom use. This view was compounded by the belief that educating about AIDS and its transmission involved explicit content. This meant churches struggled to find a middle ground between honoring their faith tenets and serving their communities.

Much of the remembered responses from this period were negative. Some religious organizations condemned those with AIDS as sinners being punished by God, refused to allow AIDS patients to participate in church activities, and ostracized members due to perceived immoral lifestyles. Fear of contracting AIDS, especially in the early days of the disease, heightened all these responses.

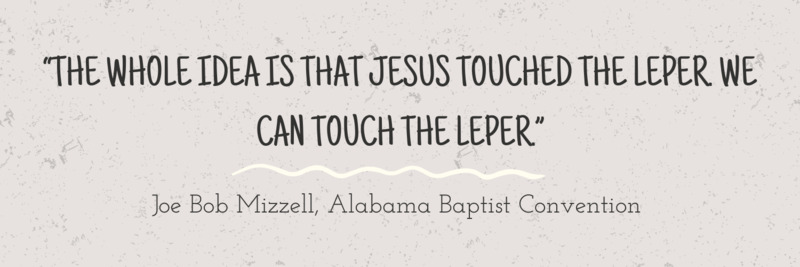

But this is not the only way that the faithful responded. Across the United States -- indeed, across the world, many religious rejected this worldview and reached out to those suffering from AIDS. God called them to care for the sick, the dying, and the abandoned. It didn't matter how they came to be sick. God's servants were meant to care for them despite this.

Fr. Thomas Stahel, for instance, pushed back against the narrative of divine retribution: "AIDS is not God's wrath poured out on homosexuals." He argued that such a "vicious idea" overlooked the fact that many non-gay individuals, including children, also contracted AIDS. He further emphasized that this condemnation "demeans God, attributing to Him the specifically vengeful intent characteristic of us, but not God. AIDS is not their problem, but ours."

The Rev. Malcolm Marler, AIDS Chaplain at the 1917 Clinic in Birmingham, AL in the 1990s stated, "It is not in my job description as a person of faith to be in judgment of another. That's God's job."

This video from the Southern AIDS Living Quilt project on Youtube expresses how many churches and faithful feel about AIDS and their role in helping with it.

In 1989, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops released the document Called to Compassion and Responsibility in response to the AIDS epidemic.

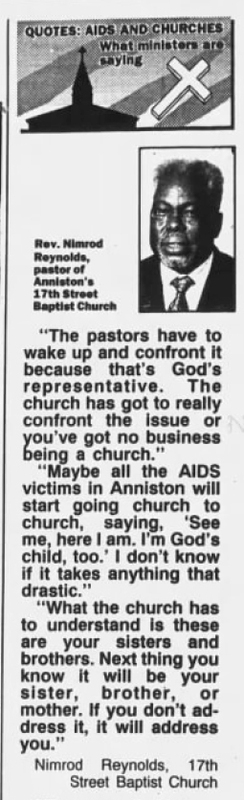

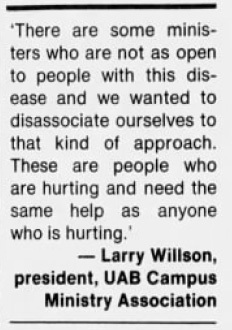

More responses of various denominations to AIDS can be seen below, published in a 1992 edition of The Anniston Star.

FAITH IN THE FACE OF AIDS

Faith plays a crucial role not only in the efforts to care for people with AIDS but also in providing comfort and support to those who are suffering from the disease.

When formally questioned about the topic, pastors believe it is a part of their role to care for the overall wellbeing, both physical and mental, of the people in their care. Supporting those with AIDS was important, and also contributing to the physical health of their congregations by helping prevent the spread of AIDS.

A study about spirituality and religion in HIV/AIDs patients showed that 75% of participants had their faith strengthened "at least a little" by their disease and that patients used "positive religious coping strategies" more than negative ones to deal with their diagnosis. Those with HIV/AIDS incorporated spirituality, as well as formal religious practice, to help bring meaning and comfort to their lives.

Most patients with HIV/AIDS belong to an organized religion, and this faith and support network helped them cope with their illness. The same structure that could help support them could also harm them if this valued community ostracized them, however. Studies have long shown that positivity and mental state can affect overall health, and the same is true with HIV/AIDS.

Others decided it was their calling to help others suffering like themselves. Volunteers with HIV/AIDS not only participated in caregiving support to other people with HIV/AIDS, they often started their own charities and initiatives, referencing their faith as an influence to do so. This helped give them meaning and helped cope with the reality of their disease.

One of these people in Alabama was Lee Simmons, who was diagnosed with AIDS in 1990 and openly admitted to having the disease in a time when most people were afraid to make their status public. He began and ran Lee Simmons' Fund for People Living with AIDS, Inc., in Mobile, to "bring a little cheer" into the lives of people with HIV/AIDS. His charity provided patients with new clothing, televisions, and radios. Simmons referred to this fund as "Make-A-Wish Foundation" for people living with AIDS.

Simmons stated to the Mobile Press Register in 1994: "AIDS is not an immediate death sentence. I am living with, not dying from, AIDS. I am not a victim."

AIDS IN ALABAMA

In the 1980s and 1990s, Alabama, like much of the United States, was grappling with the emerging AIDS epidemic. Initially, the public and government responses were characterized by fear, misinformation, and stigma. The state's healthcare infrastructure was unprepared for the rapid spread of the disease, and the lack of early effective treatments led to high mortality rates among those diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.

As the epidemic progressed, Alabama saw a significant rise in AIDS cases, particularly in urban centers like Birmingham and Mobile. Public health efforts focused on education, and prevention.

The 1917 Clinic at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) was established in 1988, and it became a leading center for HIV/AIDS care and research, and later a source of several faith-based initiatives to help those suffering from the disease.

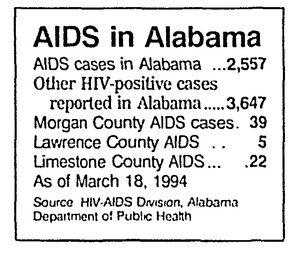

The state reported its first known AIDS case in the early 1980s. By 1989, there were approximately 868 reported cases of AIDS in Alabama. As the epidemic continued into the 1990s, the numbers grew, with nearly 4,000 cases reported by 1997.

If you would like to read more, the document AIDS in Alabama: The First 1,000 Days, from a presentation done at UAB in 1985, is available from AlabamaPublicHealth.gov.

What Pastors Thought about AIDS in Alabama in 1992

The Alabama Baptist State Convention, which encompassed the largest body of churches in the state, adopted a motion in 1987 urging the development of AIDS ministries in its churches.

Despite the State Convention's encouragement on this matter, the churches in the convention were autonomous, and groups within an individual church could still vote out HIV+ members if they chose to. However, according to Alabama Baptist State Convention official Jolene Ivy in 1989, this had not happened in a single church in Alabama.

"It is a disease and that is the way we look at that," said minister Larry Willson to the Birmingham Post Herald in 1990. He ran the UAB Campus Ministries and reached out to students and locals who might be suffering from the disease early on.

TYPES OF FAITH-BASED RESPONSES

While there were many individual and group responses from a wide array of denominations, churches, and organizations, their aid can be divided up into four different types of charity. Some groups performed only one type of aid while others provided a varied array of resources to their congregation and local community. Breaking down responses allows us to examine the intent and benefit of each type of support various groups could offer.

Many programs in Alabama resulted from partnerships and cooperation between churches, faith-based groups, and secular non-profits. Organizations such as AIDS Alabama, Birmingham AIDS Outreach (BAO), Selma AIR, AIDS Action Coalition, and even the 1917 AIDS medical clinic at UAB worked hand in hand with churches and other volunteers to serve communities in Alabama.

SPIRITUAL SUPPORT

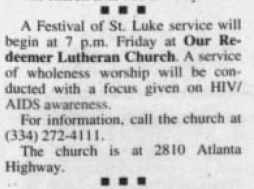

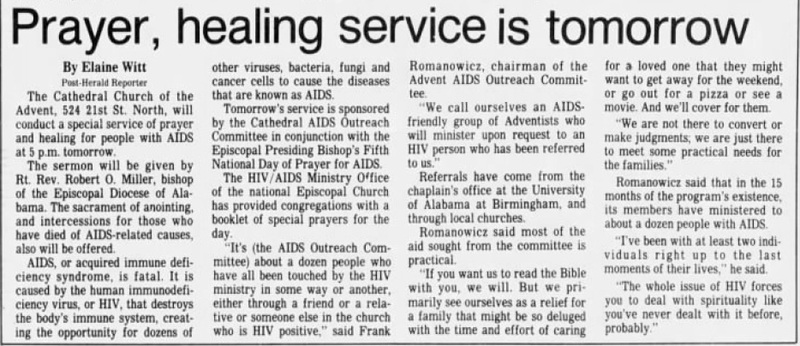

The first and most natural response from faith-based organizations in Alabama was a spiritual one. While sometimes this manifested in preaching against certain lifestyles and life situations, many churches who responded wanted to ensure that people in their communities were spiritually cared for. They offered special prayer and healing church services, started support groups at their churches, offered counseling and prayer to those affected by the disease, memorials for those who died, and participated in commemorations such as World AIDS Day. Ensuring the mental and spiritual well-being of their communities amid the AIDS crisis was a priority for these churches and faith-based organizations.

Special prayer services specifically focused on HIV/AIDS became common once the scope of the pandemic became evident, sometimes even in churches that provided no other support to victims of the disease. Sometimes they were healing services for named congregation or community members who needed support, and other times the church wished to dedicate a specific ceremony for praying for the end of the pandemic. Attendees would pray for people by name, pray for the doctors, nurses, and researchers involved in fighting AIDS, and pray for a cure. Both religious and secular organizations, including ruling councils for specific denominations and ones like The Balm of Gilead encouraged these events. They informed the community about AIDS, helped them understand it was a condition to be prayed for, comforted those who they prayed for, and helped lessen the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS amongst their congregations.

Churches also started various support groups, counseling programs, and ministries to address different spiritual support needs within their congregations and the community at large.

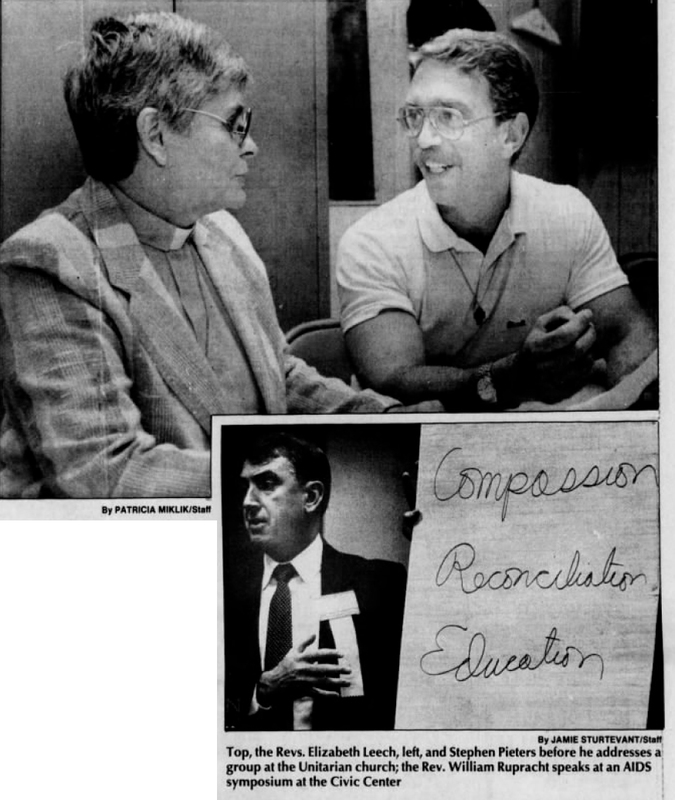

Ministers also counseled people with AIDS. For example, the Rev. Ms. Leech said she approached counseling AIDS patients as a caregiver, not a spiritual advisor. She advised patients to pray for small things, like "to help their food stay down today. To help them breath a little better."

Campus Ministries participated in spiritual support and outreach. In 1989 and 1990 the UAB Campus Ministry Association reached out to the student community in UAB's student newspaper, the Kalediscope, offering help and support to anyone with AIDS. The advertisement listed the phone numbers for six different ministers. At the time, there were United Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, Catholic and Episcopalian ministers. St Andrew's Episcopal Church, which served the UAB Campus, had support groups for HIV-infected individuals in the early 1990s.

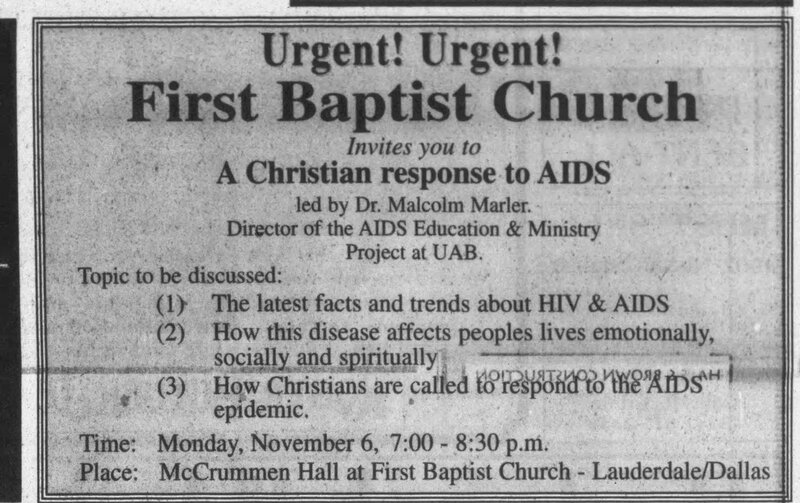

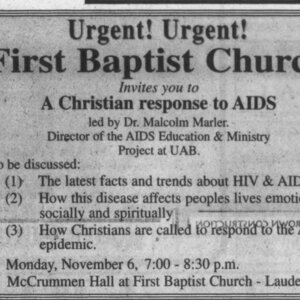

AIDS Education & Ministry Project at UAB

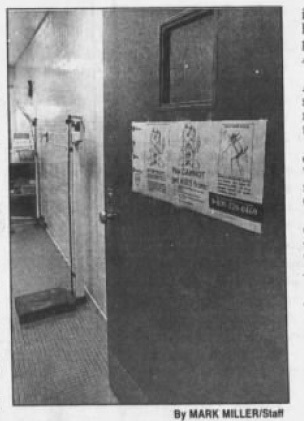

The 1917 Clinic at the University of Alabama Birmingham (UAB) was founded in 1988 by Dr. Michael Saag using a grant from the National Institute of Health. It is named after its original address at 1917 5th Avenue South.

In its early days, the 1917 Clinic quickly became known for its holistic approach to patient care, combining medical treatment with social support services. This team-based approach ensured that patients received not only medical care but also support in dealing with the social and psychological challenges of living with HIV/AIDS.

Part of this approach was the hiring of a part-time AIDS chaplain to help patients deal with their diagnosis. Dr. Saag had the vision for a HIV/AIDS community education program that targeted religious communities, to help spread HIV preventative education and bring faith organizations into the fold to help those suffering with the disease.

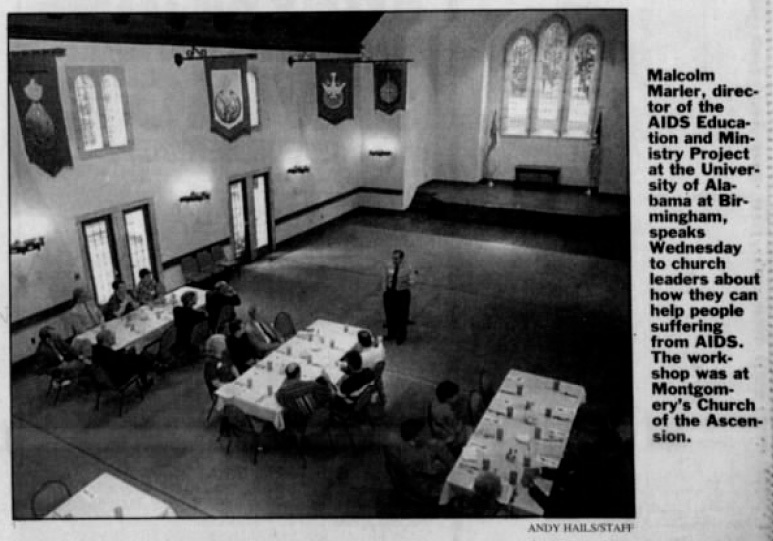

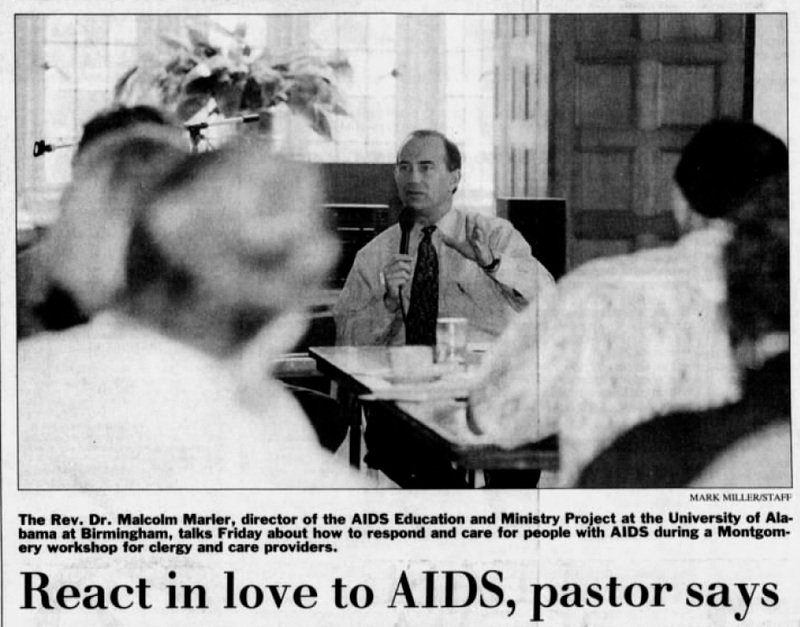

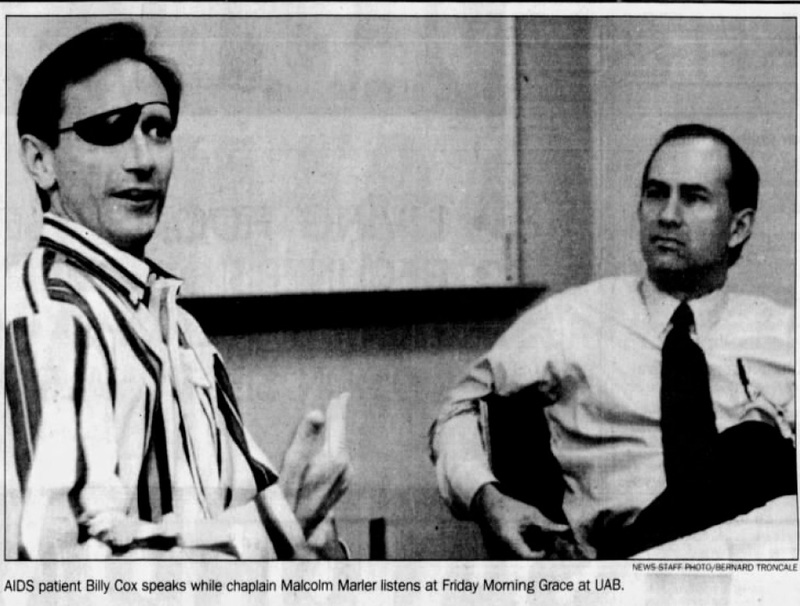

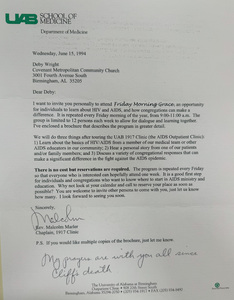

In March 1994 the Reverend Malcolm Marler began working for the Clergy Education Project, hired by Dr. Saag part-time to help reach out to local churches and spiritually care for patients in the clinic. Every week he personally visited a different church and had a one-on-one meeting with its pastor, inviting them to join the program and learn how to care for those with AIDS in their congregation and community.

As the scope of the project at the 1917 Clinic expanded, more programs and services were added under the direction of Rev. Marler, and the program evolved and becaome the AIDS and Education Ministry Project. Under this project, Friday Morning Grace started, AIDS Care Teams were founded, the newsletter Red Ribbon Reflections was published, and a resource center was created for community educators to use. In additon to teaching pastors and other church leaders, preventative educational programs for parents were founded and a program just to "train the trainers" for AIDS care began.

What started as a part-time, small-scale chaplaincy spiraled into a program that visited more than 30 states and ten different countries, all in the name of helping those infected with HIV/AIDS.

These programs are covered in more detail throughout the exhibit, matching with the type of faith-based care represented by their work

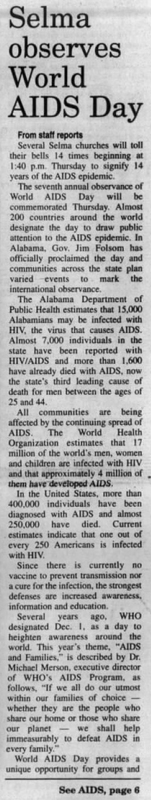

World AIDS Day

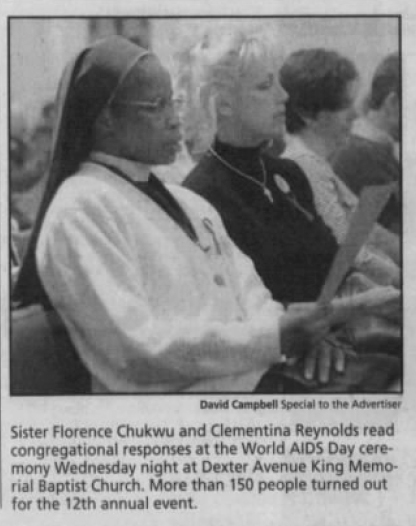

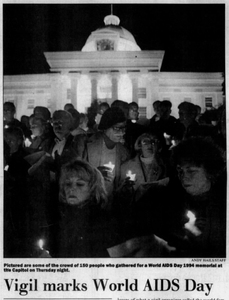

The first World AIDS Day was on December 1, 1988 to help bring attention to the AIDS pandemic, and that first year in Alabama, there was a small candlelight vigil on the Capitol steps in Montgomery. Despite it beginning from a secular organization, faith groups in Alabama quickly joined many of the planned events over the next few years. These congregations viewed the day as a way to help in the fight against AIDS.

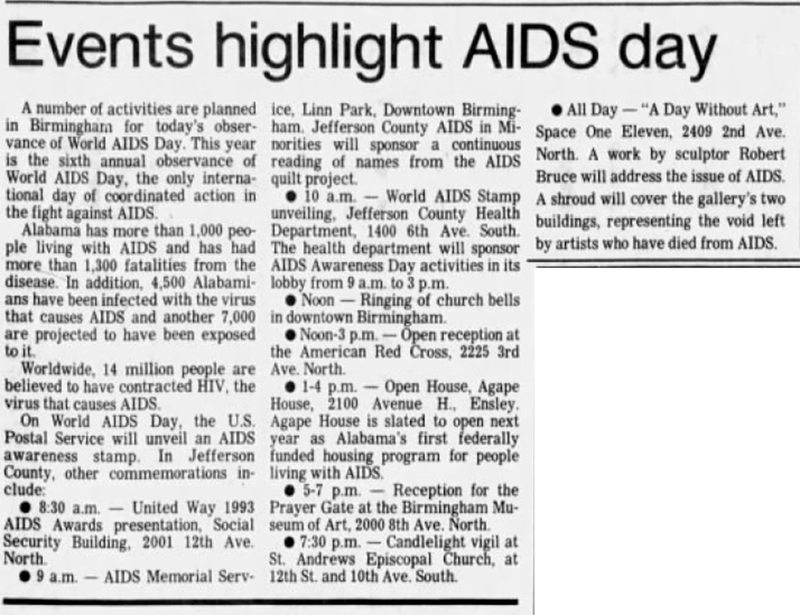

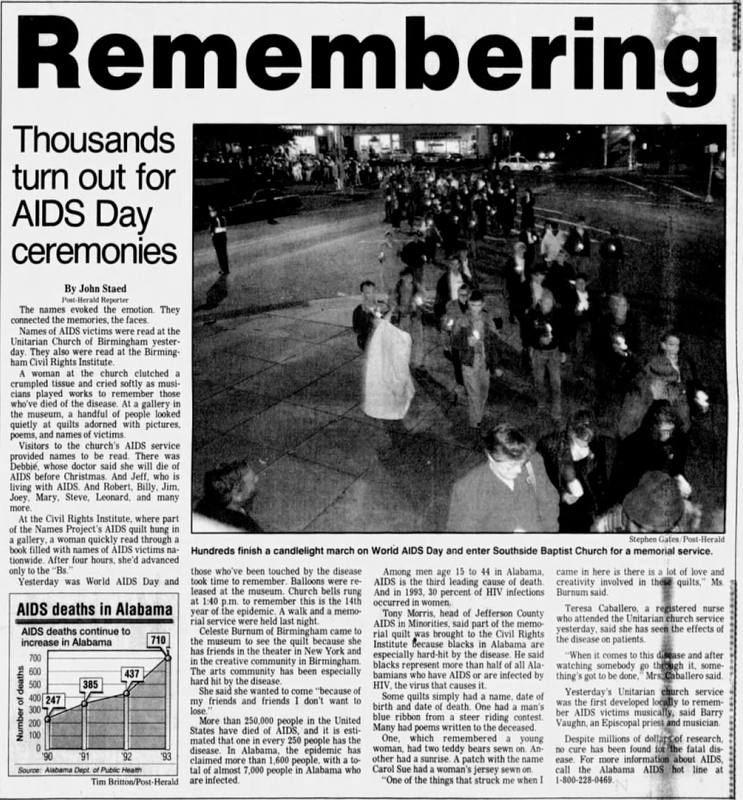

Though the White House did not start an official World AIDS Day proclaimation until 1993, churches and communities in Alabama began participating in it as early as 1989. Many denominations, as well as members of the Jewish Community, joined to remember the dead, support the living, and pray for an end to the pandemic. In 1994 in Birmingham, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Jewish and Hindu religious leaders participated in an Interfaith Memorial Service at Southside Baptist Church as part of World AIDS Day.

Baptists, Methodists, Episcipalians, Presbyterians and Roman Catholics all joined in World AIDS Day events throughout the 1990s in places like Huntsville, Birmingham, Montgomery, Dothan, Auburn, Tuscaloosa and Selma. In 1997, Rabbi Larry Mahrer of Temple Emanu-el hosted the interfaith service in Dothan with the Rev. Carl McComb of the Daleville Christian Fellowship and Rev. Russell Kendrick of the Episcopal Church of the Nativity.

Most denominations held their own prayer services in addition to participating in interfaith observances. Resurrection Catholic Church in Montgomery held a healing and memorial service as a part of World AIDS Day in 1993. Trinity United Methodist hosted a prayer service in Tuscaloosa in 1996.

During these services, the names of those who had died of AIDS were often read out loud.

Candlelight Vigils became a custom starting from the very first commemoration ceremony. Many religious people participated in these vigils, which often included a candelight walk either from a church to a ceremonty location, or to a church from a ceremony location. When a vigil ended at a church, usually an interfaith prayer service would follow it. Other churches hosted their own candlelight vigils at their locations. In Montgomery, participants would often walk to or from the capital steps. In Tuscaloosa in 1996, attendees walked from Trinity United Methodist Church to the president's mansion.

A common observance part of the World AIDS day events was for the churches in town to all ring their bells at the same time. The time was often chosen to represent the number of years of the AIDS epidemic. Churches agreed to ring the bells a set number of times, also based on the years of the AIDS crisis. In Birmingham in 1994, the churches rang the bells at 1:40pm, and rang them fourteen times, for fourteen years of AIDS. That same year, also in Birmingham, Jewish synagogues were asked to sound their shofars to mark the occasion.

Pastors often hosted opening prayers of official city events, such as Rev. Dane Smyre of First Baptist Church opening the commemoration of World AIDS Day in Dothan, Alabama in 1996.

In later years, the White House began to dim the lights "as a visual demonstration of the commitment to the fight against the AIDS pandemic and in tribute to those living with HIV/AIDS and to those who have died from AIDS". Churches often participated in this tradition too.

Other unique events were hosted, planned, or supported by faith-based groups over the years. The Unitarian Church of Birmingham hosed a music and prayer service specifically for musicians who died of AIDS in 1994. This service was the first of its kind locally, according to musician and Episcopal priest Barry Vaughn. An open house for the Agape House, special AIDS housing created by a joint effort between faith organizations and local non-profits, was part of the events in Birmingham in 1993. The Episcopal Church of the Nativity in Huntsville worked with the AIDS Action Coalition to host a holiday ceremony in 1994, where special handmade cross-stitch ornaments representing people who have died of AIDS were displayed on a Christmas tree. Family and friends of the deceased are later given the ornaments to remember their loved ones.

Fundraisers were often common on and around World AIDS Day for the various charities, both secular and faith-based, that operated in the state. This is another example of non-profits and churches working together to serve their communities. For example, The AIDS Taskforce of Alabama put on a silent auction and holiday event in 1994 to raise money, and the Cathedral Church of the Advent hosted the event for them in their parish hall.

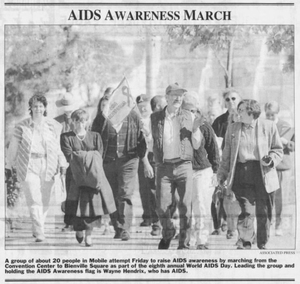

A fundraiser that would become a yearly tradition all over the state was Walk-A-Thons or AIDS Walks. Sometimes this was part of the candlelight vigil, but in many cases it was a separate walk that would raise thousands of dollars for AIDS charities in the state.

World AIDS Day in Alabama

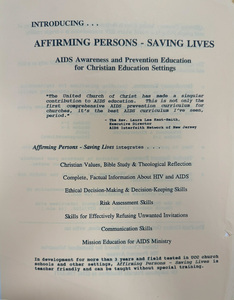

More than just providing spiritual support and charity, faith-based organizations wanted to help their communities understand AIDS better, both those suffering from it as well as the members of the general community. If their congregants understood the reality of the disease, churches could help stop the spread, reduce the stigma surrounding infection, and give their members the tools they needed to minister to the sick properly.

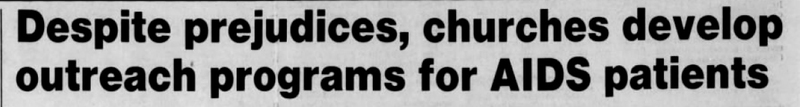

Outreach

Outreach quickly became a focus for many faith-based organizations and churches of all denominations. This outreach came in several forms - outreach to those affected by AIDS, outreach to their congregations to inform and educate them about AIDS, outreach to other ministers, and outreach to local non-profits to help in the mission of dealing with AIDS.

First and foremost, these organizations wanted to help remove the stigma of AIDS and encourage others to help with it, particularly those in their own congregations. They also wanted to serve and support people within their churches who were infected and make sure they were not ostracized from their faith family during such a difficult time in their lives. Churches did this by teaching their members about HIV/AIDS in seminars, information meetings, and support meetings. In addition to helping their members understand the nature of AIDS, they wished to help educate and stop the spread of the disease, and so many informational sessions centered on this topic.

Churches reached out to other churches in their denomination, and even in cross-denomination and interfaith efforts, to increase the availability of volunteers and call their Christian brothers and sisters to serve those in need. Pastors taught one another, invited experts into their churches, and attended special workshops to learn how to take care of the emotional, spiritual, and physical needs of those in their community with HIV/AIDS.

An example of this is the HIV/AIDS Ministries Network Focus Paper, a publication of the Health and Welfare Ministries Program Department of the United Methodist Church. This was a newsletter sent out to a "network of United Methodists and others who care about the global HIV/AIDS pendemic and those whose lives have been touched." These papers included letters and articles from HIV positive people, other pastors working with AIDS patients, updates about the pandemic, as well as guidelines and suggestions for pastoral care for those "infected or affected by HIV/AIDS."

This Methodist program also joined forces with the National Episcopal AIDS Coalition and the Lutheran AIDS Network in 1995 to hose a multi-denomination "Hope and Healing" conference in St. Louis, Missouri. This was the first joint effort by these three denominations to work together to grow their respective AIDS ministries by sharing information.

The Metropolitan Community Church branches in Mobile and Birmingham in particular reached out to the LGBT communities in their area to minister to people with AIDS in those communities. This mainline protestant church was founded in 1968 in Los Angeles, California with goal of reaching out to disaffected members of the LGBT community and bringing them into an open and welcoming denomination of Christianity that did not condemn them for their lifestyles. This meant these congregations were some of the first to further their outreach and charity to the early communities affected by HIV/AIDS. They also ran a publication called ALERT, published monthly with news from the UFMCC (Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches) on AIDS Legislation, Education, Research and Treatment.

In the early days of his jobs as the AIDS Chaplain to the 1917 clinic Malcolm Marler personally visited a different church and pastor every Friday in a personal outreach effort to help educate them and their congregations about AIDS. Eventually pastors began to come to him directly, and this mutual outreach resulted in the creation of the Friday Morning Grace program and the AIDS Care Teams, both of which are explained in detail in other portions of this exhibit.

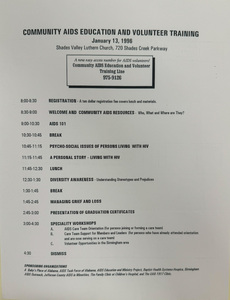

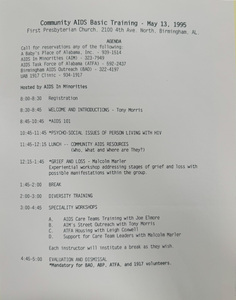

Volunteer Training

Once faith-based organizations decided they were going to step up and help those infected with HIV/AIDS, they wanted to make sure they were going about it correctly. Whether it was ministering to someone in the hospital, helping educate their congregation members, or even just being emotional support for a family, it was important that they do it right. Churches opened their doors and invited experts to come and give training sessions, encouraging those who wished to be involved in any of their AIDS support programs to attend. Pastors hosted training sessions for other pastors, to make sure everyone understood the medical facts of HIV and knew what the people they'd be caring for needed.

Many volunteers and churches wanted to make sure they were helping and not harming the people in their communities with AIDS. Volunteer training helped make sure everyone was prepared and properly educated to carry out support work in their communities.

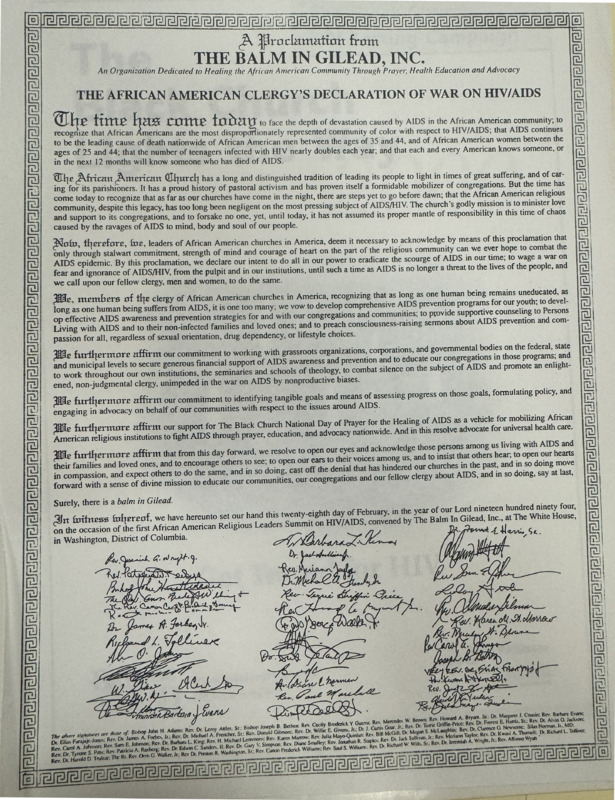

The Balm of Gilead

Founded in 1989, The Balm of Gilead provided education and support to African American communities and churches in dealing with HIV/AIDS. It is a national organization, but it had a presence in Alabama in the 1990s, including in supporting other local efforts.

The Balm in Gilead mobilized churches to become centers for education and compassionate care, helping to prevent the transmission of HIV and encouraging those infected to seek and maintain treatment.

One of their initiatives from the very beginning in 1989 was the annual Black Church Week of Prayer for the Healing of AIDS, which aimed to involve black churches in providing education and support around HIV/AIDS. This program, along with other educational and training programs, helped faith communities become more actively involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS, offering spiritual and practical support to those affected by the disease.

This organization still operates today and provides aid to the African American community, which is still disproportinately impacted by HIV/AIDS.

Friday Morning Grace

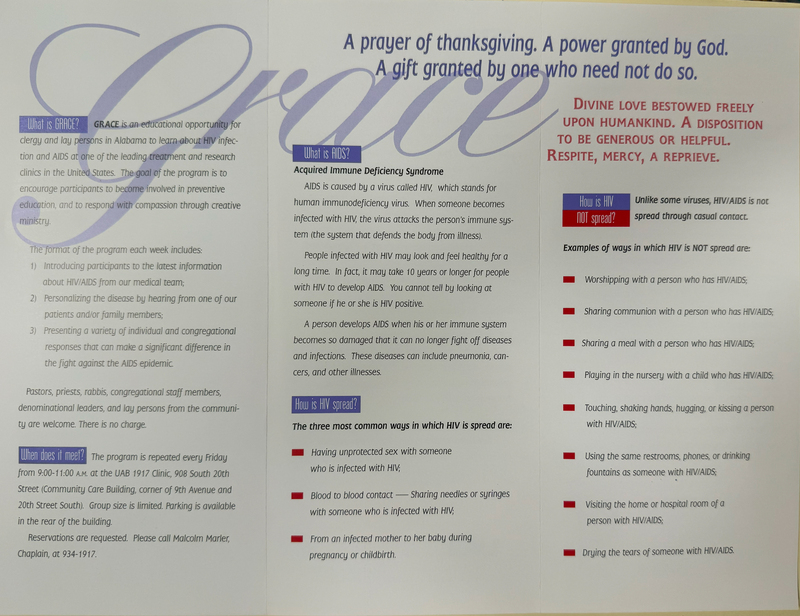

Friday Morning Grace was an outreach and educational program that became a part of the AIDS Education & Ministry Project at UAB's 1917 Clinic. It began on June 3, 1994.

Grace stood for "Giving & Receiving AIDS Compassionate Education", and the term was specifically chosen because it was one the religious community would recognize and understand. The Rev. Malcolm Marler personally invited a dozen persons in the beginning through personal visits, letters, and phone calls. For the first year, he continued this personalized effort to bring clergy to the program to spread AIDS awareness and education amongst local churches. Eventually, he no longer had to seek out attendees for the session as people eager to help started to come to the program on their own.

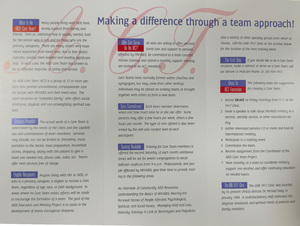

This two-hour weekly educational program was offered for both clergy and lay persons at the UAB 1917 AIDS Clinic. Meetings were limited to 12 persons to allow for "dialogue and learning together". They would tour the AIDS Outpatient clinic at 1917 AIDS Clinic, learn the basics of HIV/AIDS from a medical team member or an educator, hear a personal story from family members or an AIDS patient, and discuss congregational responses that can make a significant difference in the fight against AIDS. There was no cost but reservations were required.

By June/July 1995 more than 450 people had attended Friday Morning Grace. That summer the meetings moved to the first Friday of the month to allow the GRACE program to do more things, particularly to start a new initiative for Preventative Educational Training. This Preventative Educational Training became part of the "train the trainers" initiative.

Friday Morning Grace Provided a "head, heart, and hands" experience. Factual information (head) was shared about HIV, patients and family members told their personal stories (heart), and participants were challenged to provide HIV education and form Care Teams (hands).

This concept was also explained in other literature for the program as a three-component class: Facts, Faces, and Faith response. Facts were given by a medical team member to educate clergy and lay people on the current understanding of the disease. Faces personalized the disease by introducing attendees to a person living with HIV. Faith Response taught a variety of responses that both individuals and congregations could implement to make a difference in their communities.

PHYSICAL CARE

AIDS is a physically devastating disease, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, before effective treatments had been implemented. People infected with AIDS could suffer from severe respiratory problems, overwhelming fatigue, neurological symptoms, or tuberculosis. And with their weakened immune systems, they often contracted secondary infections, colds, thrush, and other illnesses. In the early days of the pandemic, children born with the disease usually didn’t live past their second birthday.

Physical care quickly became a necessity for many people with AIDS. Sometimes their partners or other members of their family had the disease and they struggled to care for one another. Sometimes they were abandoned by family and friends and had no one else to care for them. But even those with devoted caregivers needed assistance or a break to recover themselves, and this is where many faith-based responses would step in to help. Some organizations, such as MASS, encompassed many types of caregiving and support, while others, such as AIDS Care Teams, were more personal and provided for needs specific to the families they were serving. Faith-based organizations stepped in to provide essential physical care, offering respite, medical support, and compassionate assistance to those in need during the height of the epidemic.

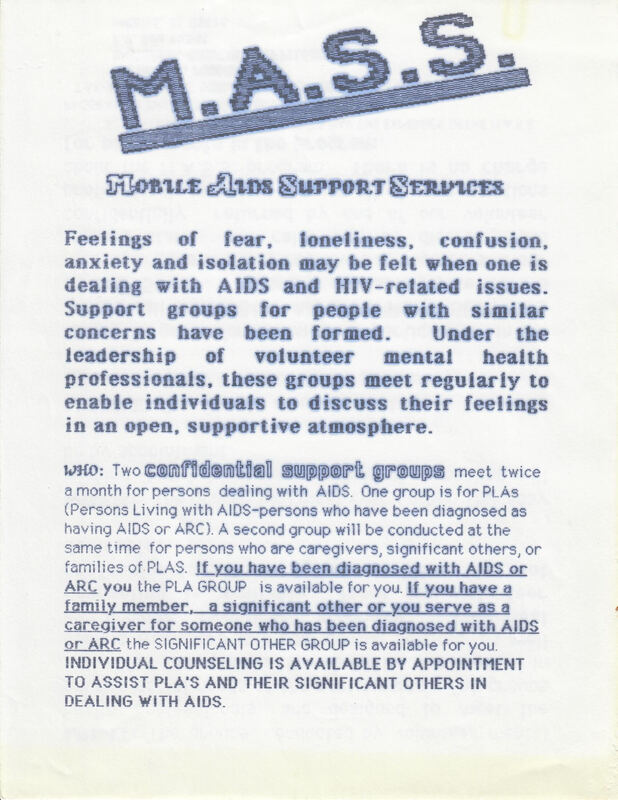

M.A.S.S.

Mobile AIDS Support Services (MASS) was founded in Mobile, Alabama in 1984 to help people suffering from GRIDS (Gay-related Immune Deficiency Syndome) Using a four-year government grant, retired school teacher Martha Wood started MASS to help the gay men in her community. It began as a hotline in the Unitarian Church on Government Street, and later the term GRIDS was dropped for the newer medical term AIDS. MASS began officially under this new name in 1987. This organization, working with the Unitarian Church, volunteers, and other churches was one of the first responses to AIDS in the state of Alabama. It started by offering emotional support to AIDS patients, and then in 1989 expanded to include case management and support.

MASS would also help patients navigate social support programs like food stamps, disability income, and other types of financial assistance during periods when their disease kept them from working. Medical Update meetings on the current state of AIDS and other educational sessions were also commonplace, often hosted by the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Mobile.

Weekly support groups hosted by MASS provided companionship and support to those who needed it. There were separate meetings for people who were HIV+, people who had progressed to AIDS, and a third group for families and friends of people with AIDS. MASS wanted to combat the isolation that often came with an AIDS diagnosis.

In 1995, MASS was actively serving 250 people in Mobile. At the time, there were 558 documented cases of AIDS in the area. That year it also expanded to support six rural counties: Baldwin, Clark, Conecuh, Escambia, Monroe, and Washington Counties, because they needed AIDS support.

MASS often worked with local churches and other organizations to raise funds for their services. Some fundraisers were unique and exciting, like the Big Guns Party in 1995, where tickets could be purchased to attend a party and laser show on the USS Alabama. Others were memorials and music services hosted at churches, like the "Kids Care: Night of a Hundred Stars" concert put on in 1996 to raise money for MASS. The rehearsals were held at the Government Methodist Church.

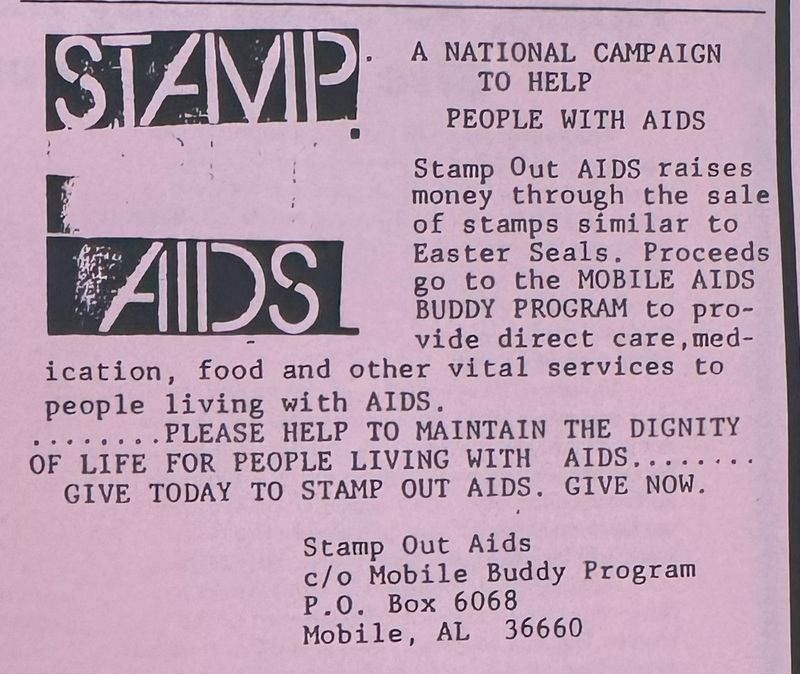

One part of MASS' program was the AIDS Buddy program. Volunteers in this program met one-on-one with their buddies at least once a week for four hours. Buddies offered emotional support, companionship, and transportation to medical appointments. They cared for pets while patients were in the hospital and delivered groceries. Volunteers often took their buddies on recreational outings or visited them in their homes to help with small tasks and watch movies, play board games, or just chat with their buddies.

In 1992, MASS buddies ran training programs in conjunction with the Mobile Bay Area Chapter of the American Red Cross. It needed more buddies to assist more than 200 clients in the program. According to MASS, an estimated 2500 people were living with AIDS in the Mobile area in January 1992.

President Bush honored Mobile AIDS Support Services as the 928th Daily Point of Light in October 1992. At the time 150+ volunteers provided services to more than 300 individuals with AIDS and their families.

Mobile AIDS Support Services continued to serve South Alabama through the 1990s, until it became AIDS Alabama South. AIDS Alabama South still offers HIV client services, including a food pantry, transportation assistance, and case management.

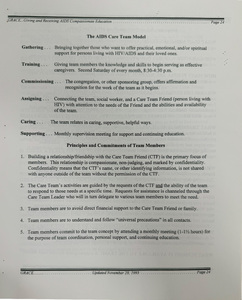

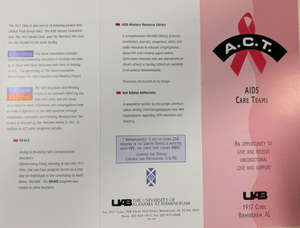

AIDS Care Teams

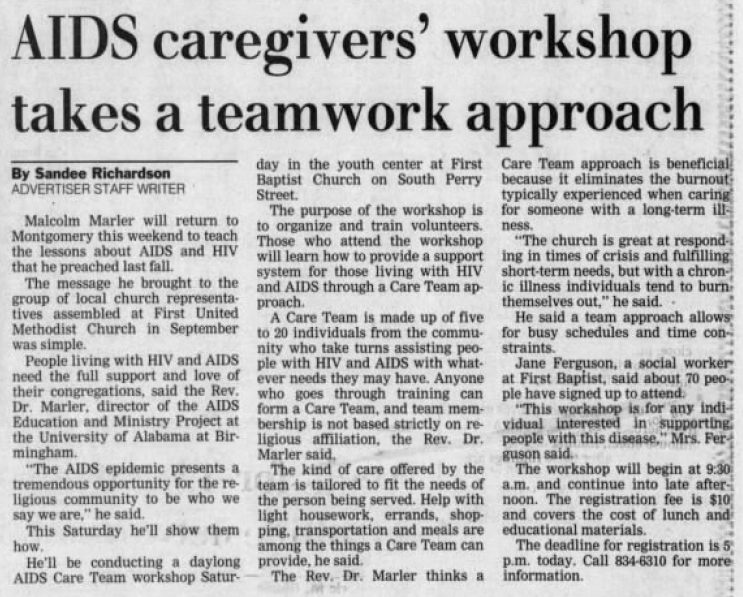

AIDS Care Teams (sometimes called ACT) in Alabama on a large scale mainly grew out of the attendees of Friday Morning Grace asking what they could do to help their communities. The concept was not a new one, but it was quickly refined and scaled up to help serve the community around Birmingham.

Each Care Team typically consisted of 10-12 trained volunteers working together to support and care for a person living with AIDS. Auxiliary members were welcome to assist the team when they could but were expected to receive the same training as regular team members. Most of these teams were based out of local churches.

Once a team was formed, they would take care of their assigned patient by bringing them food, helping with household tasks, providing transportation to doctor's appointments, and simply being a friend. Team members were also expected to hold brief monthly meetings to facilitate communication and coordination within the group.

By the end of June 1995 there were twenty-five AIDS Care Teams in the state, with cities like Florence, Jasper, Huntsville, Montevallo and Tuscaloosa beginning their own.

Eventually this model spread throughout Alabama and beyond, to other states and even other countries, to the point where the 1917 clinic had to start hosting training sessions to "train the trainers" to meet the demand for care teams.

While there are not as many AIDS-specific care teams today, the concept has expanded to include other diseases, including cancer, and many care teams still exist.

There were several rules for Care Teams when interacting with patients. They were not allowed to loan, give money to a patient, or pay for things like house repairs for their Support Team Friend. If a patient needed a particular service, then the team member would help identify community resources that could help with their problem. Care Team members were also not supposed to manage a patient's medication or give them medical advice.

Care teams were committed to "non-judging, non-proselytizing caring" and were expected to work with compassion, understanding, and acceptance. It was never appropriate to ask, "How did you become infected?", for example.

The program emphasized the importance of volunteers doing what they loved and only committing the time they could realistically manage, helping to prevent burnout. Volunteers could offer just a few hours a week or spend extensive time with a patient, including being present during their final moments to ensure they didn’t die alone.

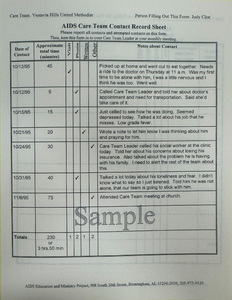

A full list of the "best practices" for support teams, as well as a sample AIDS Care Team Contact Record Sheet can be seen below. These items help illustrate what was expected of volunteers, and shows what they did as a part of this charity work.

In 1996, 90% of the 64 AIDS Care Teams in Alabama were linked with a faith congregation. After completing their training and joining an AIDS Care Team, members could "go public" through a ceremony held during a Sunday morning worship service at their church. By openly declaring their service, these volunteers not only cared for the sick but also educated the public and helped combat the stigma surrounding AIDS.

Phyllis Webb carried a green tie all over Calhoun County trying to find a suit to match it for her friend's funeral in 1996. She was a member of First United Methodist Church's AIDS Care Team, the first formed in Oxford. Her AIDS Care Team friend was dying and wanted to look nice. She was finally able to find him his suit, and yet another member of his care team was with him when he died.

Members of this AIDS Care Team included a nurse and a grocery stock boy. Most of the team worked full-time. They prayed with a family where both parents were HIV+, cooked them meals, and repaired their mobile home.

Harry Wingfield, who became friends with members of a Birmingham Methodist Church care team, ended up in the hospital for pneumonia twice. Both times, his Care Team took care of his flower garden while he was unable to, weeding the beds and making sure it survived his illness.

"Even when I'm feeling great, they are still supportive. That's how God reveals himself. They end up being the face of God," said Harry Wingfield about his AIDS Care Team in 1996 in an interview with The Anniston Star newspaper.

These are just two AIDS Care Teams amongst many over the years, and two personal stories to show what kind of work these teams did.

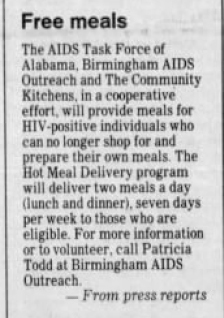

The Community Kitchens

Originally known as The Red Door Soup Kitchen, Father Maurice Branscomb, with the support of St. Andrew's Parish, founded The Community Kitchens in 1980 to provide meals to those in need in Birmingham. In 1990 there were three Community Kitchens: one at Grace Episcopal Church in Woodlawn, one at Christ Episcopal Church in Fairfield, and the original location at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church in Southside.

Summer of 1996, The Community Kitchens teamed up with The AIDS Taskforce of Alabama and the Birmingham AIDS Outreach to offer meals to people with AIDS seven days a week. A hot lunch and dinner were delivered to those who struggled to shop for groceries and cook their own meals.

The Community Kitchens continues to operate in Birmingham today, though it is now a community-based nonprofit and is no longer affiliated with its founding Birmingham Episcopal churches.

HOUSING

The HIV/AIDS epidemic created significant financial insecurity for those affected. In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, many people, unable to work due to their symptoms or facing discrimination, lacked family support or assistance with housing.

Many individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS faced job loss due to discrimination and the debilitating nature of the disease, leading to severe economic hardships. The cost of medical treatments, combined with the loss of income, often resulted in homelessness.

Before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, people with HIV/AIDS had limited legal protection against discrimination. This lack of protection exacerbated their financial instability, as employers could legally fire them or refuse to hire them based on their health status. As a result, securing and maintaining housing became even more challenging for those living with HIV/AIDS. Faith-based organizations stepped in to fill this gap, recognizing that housing was essential for the physical and emotional well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS. These organizations provided emergency shelters, long-term housing solutions, and financial assistance for rent and utilities. They also often combined personal care with the housing support, helping feed and nurse those who found themselves in AIDS housing.

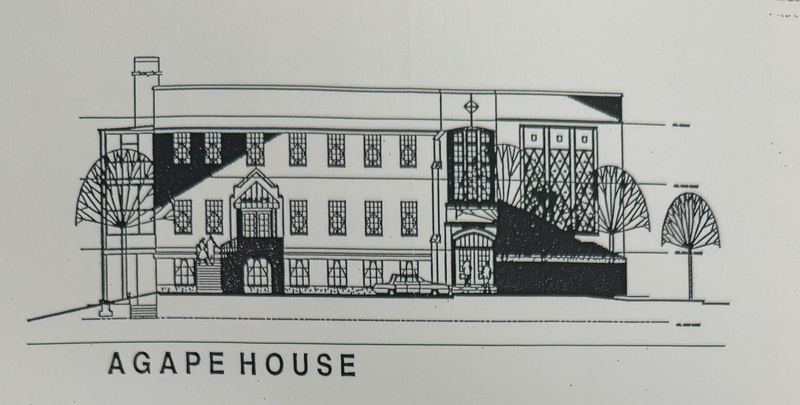

AGAPE House

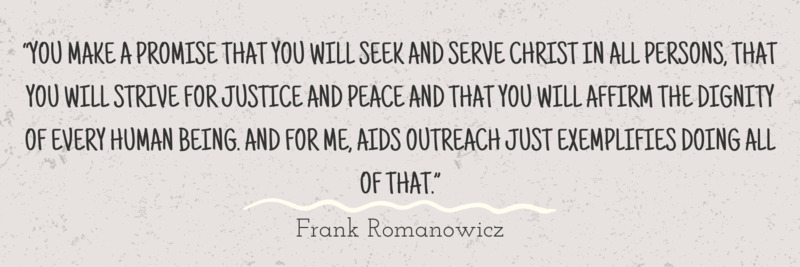

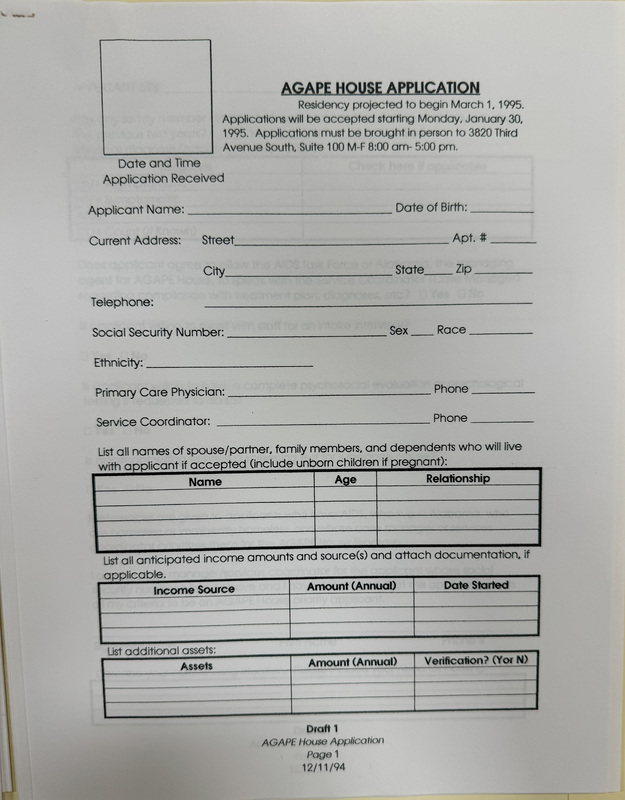

When Frank Romanowicz, an AIDS activist watched his AIDS buddy live in five different places the year before he died (including boarding homes, two motels, and finally a small unfurnished apartment), he knew he had to find a way to help support those with AIDS find stable housing. AIDS patients were sometimes forced to stay in hospitals because they had nowhere else to go.

Romanowicz was a long-time AIDS volunteer through his church, Advent Episcopal Church, and the head of the housing committee for The AIDS Taskforce of Alabama. He also founded the AIDS Task Force of the Episcopal Diocese in Alabama, and "did anything that needed to be done" to help care for people with AIDS in his community. After being laid off from just job, he spent all his time volunteering for AIDS support charities. He was the head of the AIDS Outreach Program at Advent Episcopal Church and also volunteered at the St. George HIV Clinic at Cooper Green Hospital. With his experience, he was determined to make sure that those in need had a place to go.

In 1992, the AIDS Taskforce of Alabama identified housing as a major area of need being unserviced in Alabama. In that same year a government study found that there were at least 30 residents in Birmingham disabled by AIDS and unable to afford housing. Randall Russell, the executive director of the AIDS Task Force of Alabama stated in 1993 that the opening of the Agape House would bring the total available units to 30, but the projected need for special AIDS housing was estimated to be 324 units.

At around the same time, Olivia Hill, the director of the Office for Black Ministry of the Catholic Diocese of Birmingham was conducting a study of health services needs in the Birmingham area, and at the time there was no housing provided in the state for people with HIV/AIDS. She decided to help meet that need for the area, and eventually she and Romanowicz connected to make this happen.

The AIDS Taskforce of Alabama worked jointly with the Episcopalian St. Andrew's Foundation and the Catholic Diocese of Birmingham to establish the AGAPE House in Ensley in Birmingham, Alabama. The leaders of the Birmingham Diocese agreed to offer the Agape House and its property to the AIDS Taskforce of Alabama to help meet the housing needs for those with HIV/AIDS, while the Taskforce dealt with grants, renovations, and fundraising. BAO, Birmingham AIDS Outreach, also volunteered services to the project.

The Agape House building was originally St. Anthony's Church, built in 1929. The church later converted it into a retreat center and named it Agape House. St. Anthony's gave the AIDS Task Force a 99-year lease on the building and allowed renovations to it to created the needed apartments. Volunteers decided to keep the building's name in honor of their help with the project.

Agape House recieved a 1.8 Milliion dollar grant from HUD to create a home for AIDS patients. Half the grant was used to renovate the building, and the other half kept in reserve for a 20-year period to be used for rental assistance. It was the first federally funded housing for AIDS patients in Alabama. At the time, only twenty-five other similar housing projects existed in the United States.

Renovations started on the house in August/September 1994 with a goal of opening in March 1995. A groundbreaking ceremony took place on Wednesday, August 17, 1994.

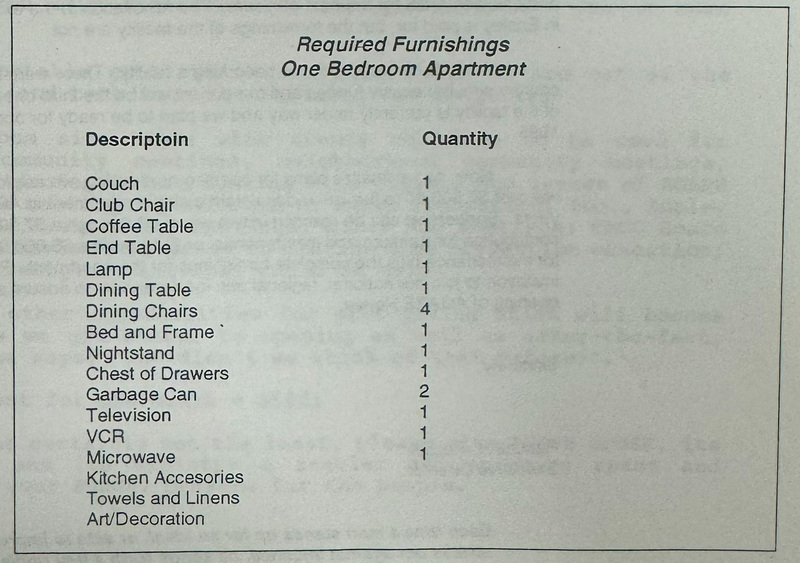

It provided eighteen, handicapped accessible one bedroom apartments for long term residency, and the apartments came furnished. All utilities were paid by the AGAPE Foundation, and the rent was capped at $227 a month. Those with HIV/AIDS were given priority for the housing.

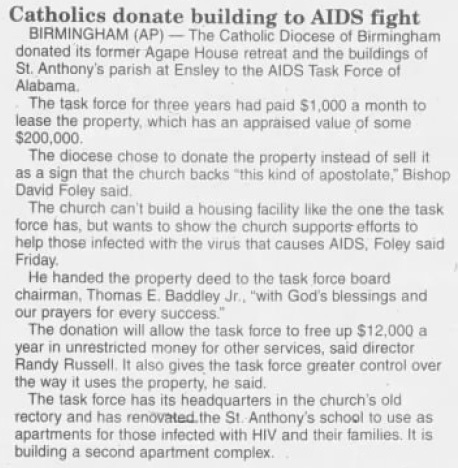

In 1998, the Catholic Diocese of Birmingham donated the Agape House's building and properties to the AIDS Task Force of Alabama. This donation allowed the taskforce to stop paying rent and freed up $12,000 dollars a year for the Taskforce to put to other uses. Bishop David Foley stated that the Diocese chose to donate the property to show that the Catholic Church supports "this kind of apostolate."

Agape House still operates today, providing affordable housing to those in the Birmingham area.

Downtown Rescue Mission

The Downtown Rescue Mission in Huntsville, Alabama was founded in 1975 to provide essential services like food and emergency shelter to those in need in North Alabama. It is a faith-based charity and emphasizes "Christ-filled care," aiming to help individuals overcome their struggles through spiritual support and compassionate service.

But in the 1990s, it stepped in to provide a different kind of service to one man: an address.

Limestone Correctional Facility in Alabama became a flashpoint in the AIDS crisis. The facility housed a significant number of inmates diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, often under challenging conditions that included inadequate medical care, poor living environments, and severe stigma.

And HIV-positive inmate Edward Easley languished in this separate unit for HIV positive prisoners for 14 months past his parole date because he did not have a home to go to in Alabama.

In February 1997, Easley was finally pulled out of prison by the Downtown Rescue Mission, who provided him with an address. Roy Fogg, the director of ministries at the mission, received a letter from Easley addressed to "anyone out there that cares."

With a home and address at the Rescue Mission, Easley was able to leave Limestone Correctional Facility and eventually get his own apartment. At the time he claimed 40 of the 237 inmates in the HIV unit were being kept from release because of a lack of an address, as well as four women at Julia Tutwiler Prison in Wetumpka. The Warden of Limestone Correctional Facility claimed that these numbers were overstated and "no more than 15 people" were waiting for release.

After his release Easley proposed the creation of halfway houses for HIV positive inmates to help them get their parole release on time, citing his faith as a reason for wishing to serve his fellow prisoners after his release. Both the AIDS Taskforce of Alabama and the AIDS Action Coalition expressed interest in supporting these houses.

However, despite the need for the housing, Easley's proposal encountered considerable resistance. Leaders stated that they didn't want Huntsville to become a "dumping ground" for HIV positive inmates, and Easley's own status as a parolee complicated the matter. As a result, the proposal did not lead to the establishment of the halfway houses as initially envisioned. This reflects broader issues concerning the care and integration of HIV-positive individuals, particularly those within the criminal justice system, and how even with non-profits and faith support, housing was often a struggle.

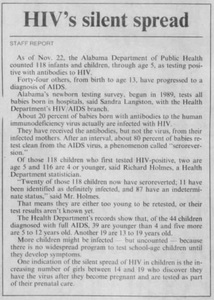

A Baby's Place

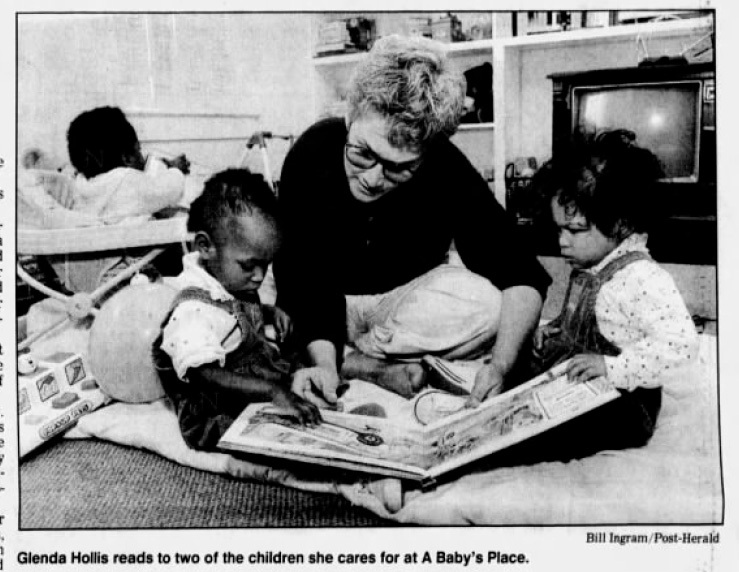

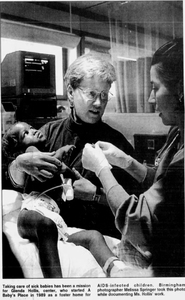

A Baby's Place opened in an undisclosed Birmingham neighborhood in October 1989 in conjunction with Birmingham AIDS Outreach. Fears of HIV positive, medically fragile babies abandoned or orphaned being stuck in limbo living in a hospital drove the creation of this service organization and special foster home. Staff members included a cook and a chaplain, and volunteers both provided supplies for the home and helped care for the children living in it.

The organization as a whole served children from birth to age 13 years that were infected by HIV/AIDS, or who had a caregiver suffering from the disease. It provided education programs, in-house foster care for children who needed it, material support to HIV/AIDS families with children, and social support.

The main mission was to provide permanent long-term placement for HIV+ infants who were either abandoned or orphaned, as well as short-term care for children whose parents were sick or hospitalized with HIV/AIDS. It also provided hospice care for HIV+ infants and other medically fragile babies.

In 1991, six babies were living in the foster home. By 1994, 26 children had been cared for at A Baby's Place. Other young children with AIDS used the house as a "mother's morning out", a program to learn and play somewhere safe with their compromised immune systems. Both local and rural families received help with food, bills, and other caregiving support related to the special needs of families with AIDS.

By the end of the 1990s, A Baby's Place was less about housing and more about community support for families. An emphasis on keeping families together, improvements in medical care and treatment for HIV/AIDS, and small numbers of infected babies being abandoned in hospitals influenced the shift in focus for the charity. It ceased being a foster home in 1997 and the property was sold to the AIDS Taskforce of Alabama to house people with AIDS. From its headquarters in Southside Baptist Church, the organization continued to provide housing support, food and diaper assistance, and help with medical expenses.

As the ninties ended and medical treatments and medication for HIV/AIDS improved, the overwhelming need for many of the caregiving services began to fade. Today, the HIV virus can be suppressed so those infected with it can live normal lives, without the debilitating physical symptoms of the disease. Education and the outreach efforts to humanize those suffering from the disease have succeeded in erasing widespread fear, stigmatism, and ostracization related to the disease.

New HIV infections are down 59% since the peak in 1995. Deaths from AIDS have dropped 69% worldwide since the peak in 2005. Activist, medical, and caregiving efforts have made an impact on the disease.

Many of organizations and services still exist today, but their missions have expanded and their focus is not necessarily centered on AIDS. Nonprofits combined, care teams expanded into helping those with other illnesses. Faith-based Organizations in Alabama stepped up to fill a need in the first two decades of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

The journey of faith-based organizations in Alabama, from offering spiritual comfort to providing practical support, highlights the role these groups played in public health. Their work has shown that addressing the AIDS pandemic requires a holistic approach that includes both activism and caregiving.

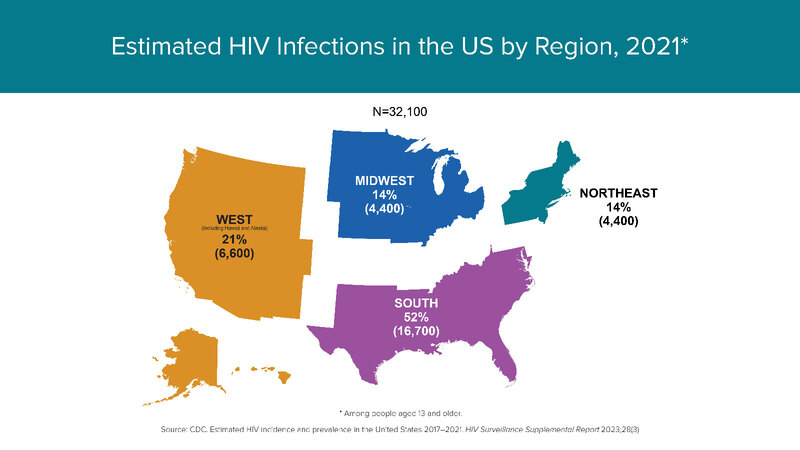

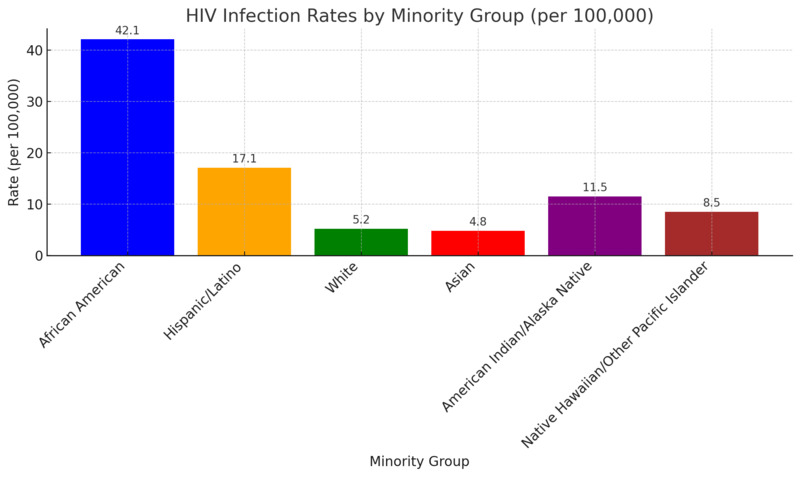

More than 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV/AIDS. Approximately 14,700 of them live in Alabama. The South still accounts for more than half the new HIV infections in the United States. Black/African people and Hispanics account for a disproportionate number of new infections, and the disease continues to greatly affect minority communities.

In Alabama during the 1980s and 1990s, the primary focus in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic was on providing care and education rather than direct activism. Faith-based organizations emphasized the importance of compassionate care, seeking to emulate the teachings of Jesus by caring for their community members with dignity and love. These organizations stepped in to offer critical support, including physical care, housing assistance, spiritual guidance, and educational programs.

Their efforts were rooted in the belief that serving others was a fundamental expression of their faith. By offering medical support, counseling, and essential services, they aimed to improve the quality of life for those affected by HIV/AIDS. Educational initiatives were also vital, as they worked to spread accurate information about the disease, reduce stigma, and promote prevention measures within their communities.

While significant strides have been made in the fight against HIV/AIDS, the journey is far from complete. The continued prevalence of HIV/AIDS in minority communities calls for renewed efforts in prevention, education, and care. We must commit to addressing the ongoing challenges, ensuring that the lessons of the past inform our efforts to create a healthier, more equitable future for all.

"Love one another as He has loved us."

Acknowledgments

All RCEU projects were sponsored in part by the Alabama Space Grant Consortium, the UAH Office of the President, Office of the Provost, Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development, the College of Science, the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, and the College of Education. I would like to thank Charlie Gibbons, Reagan Grimsley, and Drew Adan from UAH Archives and Special Collections for their help and feedback, as well as the Birmingham Public Library Archives and the Invisible Histories Project. I’d also like to thank the Rev. Malcolm Marler, the AIDS chaplain at the 1917 AIDS Clinic at UAB for providing items from his personal collection to the exhibit and for giving me his time and conducting an oral history interview for the project.

Sources

Abara, Winston, et al. "A Faith-Based Community Partnership to Address HIV/AIDS in the Southern United States: Implementation, Challenges, and Lessons Learned." Journal of Religion and Health 54, no. 1 (February 2015): 33-45.

"A Baby's Place: AIDS-Infected Babies Find Love from a Special Group of People." The Birmingham Post-Herald, September 29, 1990.

"AIDS." The Mobile Press Register, October 28, 1994.

AIDS Alabama South. "AIDS Alabama South." Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.aidsalabamasouth.org/.

"AIDS Care Teams." In Marge Ragona Collection, AIDS Education and Ministry Project. 2174.2.27. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"AIDS Care Teams Handout." In Marge Ragona Collection, HIV-1917 Clinic. 2174.2.38. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"AIDS Foster Home Closes." The Birmingham Post-Herald, June 20, 1997.

"AIDS Ministry Is a Job for Church." The Birmingham Post-Herald, May 21, 1993.

"AIDS Program 928th 'Point of Light'." Mobile Register, October 20, 1992.

"AIDS Support Is Topic in Friday Call." The Birmingham Post-Herald, June 17, 1994.

"AIDS Symposium Addresses Caring, Prevention." The Montgomery Advertiser, October 6, 1994.

"AIDS Caregivers' Workshop Takes a Teamwork Approach." The Birmingham Post-Herald, February 1, 1996.

"Answered Prayer: How One Church Helped." The Anniston Star, October 10, 1992.

"An Open Door for the Dying." The Birmingham Post-Herald, December 25, 1992.

"Bush Will Honor AIDS Support Services." The Mobile Press, October 16, 1992.

Carnahan, Rev. Charles. "Letter about the Hope and Healing Conference in St. Louis." June 2, 1992. In Marge Ragona Collection. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Care Team Orientation Handout Booklet. The Care Team Network, UAB. Personal collection of Malcolm Marler.

"Catholics Donate Building to AIDS Fight." The Selma Times-Journal, September 6, 1998.

"Church Support Urged in Battle Against AIDS." The Anniston Star, November 5, 1990.

CNN. "AIDS in the 90s: ‘I wasn’t going to die miserably’." CNN.com, June 1, 2011. https://www.cnn.com/2011/HEALTH/06/01/scruggs.hiv.aids/index.html.

Community Kitchens of Birmingham. "Community Kitchens of Birmingham." Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.communitykitchens.org/.

"Concerns of Blacks Targeted." The Birmingham Post-Herald, May 22, 1992.

Cotton, Sian, Christina M. Puchalski, Susan N. Sherman, Joseph M. Mrus, May H. Peterman, Judith Feinberg, Kenneth I. Pargament, Amy C. Justice, Anthony C. Leonard, and Joel Tsevat. "Spirituality and Religion in Patients with HIV/AIDS." Journal of General Internal Medicine 21, Suppl. 5 (2006): S5-S13.

"Dead Remembered at AIDS Vigil." The Montgomery Advertiser, December 1, 1995.

"Despite Prejudices, Churches Develop Outreach Programs for AIDS Patients." The Montgomery Advertiser, October 20, 1989.

"Five Years Later, 'A Baby's Place' Still Overflows with Love, Hope." The Birmingham Post-Herald, October 15, 1994.

"Former Inmate Looks to Help Parolees with AIDS." The Selma Times-Journal, July 21, 1997.

"Foster Home for HIV-Infected Babies Shows Love Does Work." The Dothan Eagle, December 3, 1991.

"Fundraising Letter for the Agape House." October 31, 1994. In Marge Ragona Collection, Agape House. 2174.02.28. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"God Is on the Side of Suffering." The Decatur Daily, March 25, 1994.

"Grant to Help Get Home for AIDS Patients." The Birmingham Post-Herald, October 7, 1992.

Grace: Giving & Receiving AIDS Compassionate Education Booklet from the AIDS Education and Ministry Project. UAB 1917 Clinic. In Marge Ragona Collection, AIDS Education and Ministry Project. 2174.2.27. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"Group Forms AIDS Network." The Huntsville Times, June 4, 1994.

"Group Reaches to AIDS Victims." The Birmingham Post-Herald, October 12, 1990.

"Homeless AIDS Patients to Have Place to Go Soon." The Mobile Register, December 6, 1989.

"Infected Patients to Have a Home." The Birmingham Post-Herald, August 17, 1994.

Invisible Histories Project. "In Honor of World AIDS Day 2020." Accessed August 19, 2024. https://invisiblehistory.org/exhibits/in-honor-of-world-aids-day-2020/.

"Kids Will Sing to Support AIDS Services." Mobile Register, August 9, 1996.

Lambert, Shirley. "Letter to CMCC Board Re: Care Teams." May 13, 1995. In Marge Ragona Collection. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Lichtenstein, Bronwen. "Secret Encounters: Black Men, Bisexuality, and AIDS in Alabama." Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14, no. 3 (2000): 374-393.

Marler, Malcolm. "Letter to All Care Team Members, Re: Contact Record Sheets, Training Program/Support." December 20, 1995. In Marge Ragona Collection, AIDS/HIV. 2174.2.23. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Marler, Malcolm. "Letter to Deby Wright." June 15, 1994. In Marge Ragona Collection, HIV Ministry. 2174.2.38. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Marler, Malcolm. "Letter to Marge Ragona about Support and Training for AIDS Care Teams." April 21, 1995. In Marge Ragona Collection, HIV Ministry. 2174.2.38. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Marler, Malcolm. Interview by Morgon Newquist. July 22, 2024. Birmingham, Alabama.

"Ministers Learn to Deal with Members with AIDS." The Decatur Daily, October 12, 1991.

"Ministers Struggle with AIDS Challenge." The Anniston Star, October 10, 1992.

"Mobile AIDS Support Expands Service Area." The Mobile Press, April 17, 1995.

"Mobile AIDS Support Services Helps Patients Fight Isolation." The Mobile Press Register, vol. 3, no. 27.

Petro, Anthony M. After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality, and American Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Pichon, L.C., et al. "An Exploration of U.S. Southern Faith Leaders’ Perspectives of HIV Prevention, Sexuality, and Sexual Health Teachings." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16 (2020): 1-17.

"Prayer, Healing Service Is Tomorrow." The Birmingham Post-Herald, October 12, 1990.

"Public Disclosures of Private Realities." The Birmingham Post-Herald, October 12, 1990.

"Public Views Agape House." The Birmingham Post-Herald, December 2, 1993.

Romanowicz, Frank. "Memorandum to Covenant Metropolitan Community Church Board of Directors, Subject: Agape House - Opportunities for Giving." April 10, 1995. In Marge Ragona Collection, Agape House. 2174.02.28. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"React in Love to AIDS, Pastor Says." The Montgomery Advertiser, September 29, 1995.

"Red Ribbon Reflections, June/July 1995." In Marge Ragona Collection, HIV Support Group. 2174.2.37. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"Red Ribbon Reflections Newsletter, Oct/Nov/Dec 1995." In Marge Ragona Collection, AIDS and Ministry Project. 2174.02.27. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

Russell, Randall H. "Fundraising Letter for the Agape House." October 31, 1994. In Marge Ragona Collection, Agape House. 2174.02.28. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"Scriptures, Hope Mark AIDS Service." The Montgomery Advertiser, December 1, 1999.

"Seminar Teaches Churches How to Help AIDS Patients." The Anniston Star, September 2, 1994.

"Summer 1988 MCC Mobile Newsletter." In Marge Ragona Collection. Birmingham Public Library Archives, Birmingham, AL.

"Tiniest Victims." The Montgomery Advertiser, December 5, 1993.

The Balm of Gilead, Inc. "The Balm of Gilead, Inc." Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.balmingilead.org/.

"UAB Filled Void in Care as AIDS Grief Rose in 1980s." AL.com, June 19, 2011. https://www.al.com/spotnews/2011/06/uab_filled_void_in_care_as_aid.html.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. "HIV.gov." Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.hiv.gov/."Vigil Makes World AIDS Day." The Birmingham Post-Herald, December 2, 1994.

"Volunteers Minister to Inmates with AIDS." The Huntsville Times, December 17, 1988.

Vider, Stephen. "Public Disclosures of Private Realities." The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (May 2019): 163-189.

"Where They Stand." The Anniston Star, October 11, 1992.

Wheeler, David L. "Faith in the Face of AIDS." The Chronicle of Higher Education 41, no. 36 (May 19, 1995).

"World AIDS Day: Local Groups Honor Memory of Those Who Died." The Huntsville Times, December 1, 1994.